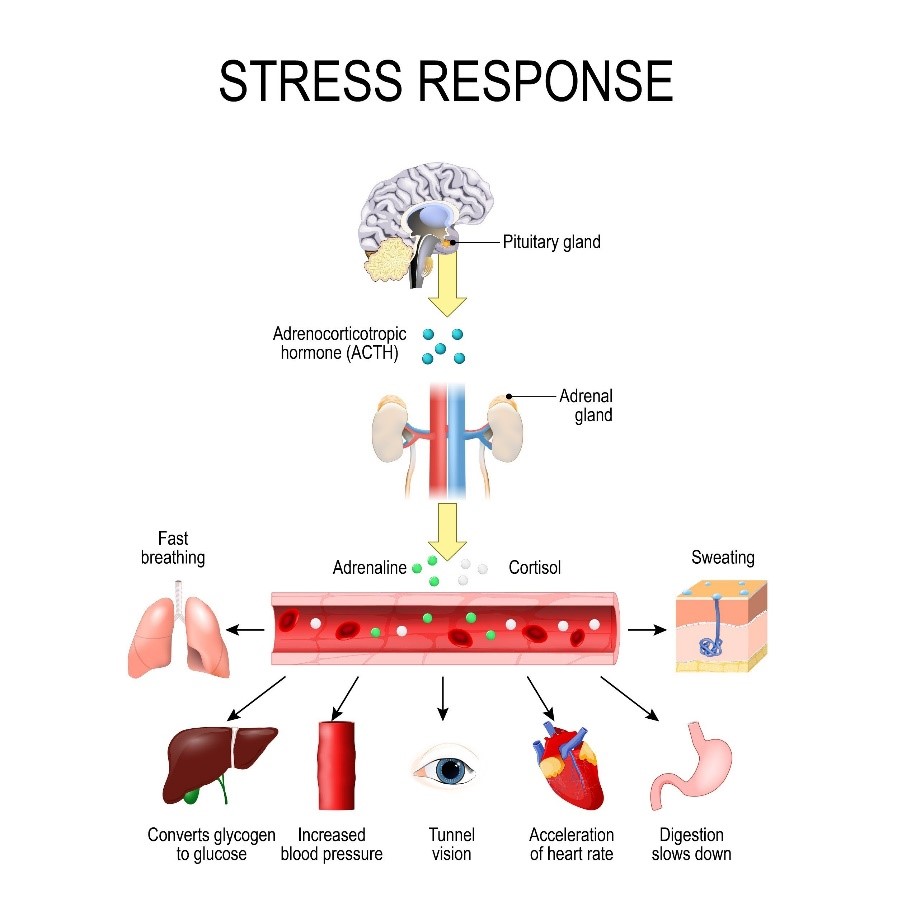

Research continues to mount showing that stress affects our health and well-being. The various daily experiences we face that lead to stress set off a cascade of physiological responses that, when experienced over a lifetime, can lead to diabetes, hypertension, and eventually heart attack and stroke.

Research continues to mount showing that stress affects our health and well-being. The various daily experiences we face that lead to stress set off a cascade of physiological responses that, when experienced over a lifetime, can lead to diabetes, hypertension, and eventually heart attack and stroke.

The effects of stress experienced over a lifetime are especially apparent for any individual who experiences discrimination or trauma due to identifying as a member of a minority group. The Minority Stress Model detailed in racial and ethnic groups and further expanded to include sexual and gender minorities (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer [LGBTQ] individuals) posits that LGBTQ folks and other minority groups are at greater risk for health problems, especially depression, because of the stigma, discrimination, and victimization they experience over their lifetime.

Experiences of minority stress stem from expectations of rejection, concealment (if possible) of one’s minority status, internalized homophobia and/or transphobia, and experiences of physical, mental and social harm. Concealment of one’s minority status is particularly unique to sexual and gender minority populations, who may also experience other forms of minority stress based on race/ethnicity, gender, and social class. Evidence linking minority stress and physical health outcomes is somewhat mixed, but in SGM populations the findings (especially for depression and other mental health problems) are fairly strong.

While minority stress may be more distal (timing of exposure happens earlier in life), there is likely a cumulative effect over the life course given everyday experiences of discrimination that could result in a greater risk for cardiovascular disease and other co-morbid conditions later in life.

Several studies have recently highlighted the measurable effects of stress among sexual and gender minorities:

- Lifetime Trauma and Cardiometabolic Risk in Sexual Minority Women

- Body composition and markers of cardiometabolic health in transgender youth compared to cisgender youth.

- Assessing gender identity differences in cardiovascular disease in US adults: an analysis of data from the 2014-2017 BRFSS.

- Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender

At the AHA Scientific Sessions, Billy Caceres PhD similarly outlined these effects in his presentation “Minority Stress, Social Support, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Persons.” Using cross-sectional data from Project AFFIRM, which consists of a diverse sample of transgender people recruited from three cities, Dr. Caceres and colleagues examined the association of minority stressors, social support, and gender-affirming hormone use with self-reported cardiovascular risk factors (i.e., tobacco use, risky drinking, short sleep duration, physical inactivity, and body mass index [BMI]) adjusted for demographic characteristics. They then examined whether social support moderated the association of minority stressors and CVD risk factors. They found that experiences of discrimination were associated with higher rates of risky drinking and lower rates of adequate sleep duration. Internalized transphobia was associated with lower rates of physical activity.

Utilizing the Minority Stress Model to identify potential interventions to reduce the harmful effects of discrimination and subsequent stress, a recent study explored the effects of support for sexual minority youth (i.e. lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer):

Researchers used data came from Wave IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) and created stratified linear regression models examining if father and mother support moderated the association between discrimination and inflammation (i.e. CRP) among sexual minorities and heterosexuals. What they found was that father support significantly moderated the association between discrimination and CRP among sexual minorities but not heterosexuals. Sexual minorities with higher father support and who experienced discrimination had lower CRP as compared to those with lower father support and who experienced discrimination; mother support did not moderate the association between discrimination and CRP among either sexual minorities or heterosexuals.

The research findings fit the current Minority Stress Model, demonstrating that father support may mitigate the negative effects of stress from discrimination on subsequent inflammation among sexual minorities. Future research ought to examine additional protective factors that could inform the development of interventions mitigating the harmful effects of discrimination and stress on subsequent cardiometabolic health.

Dr. Caceres’ research presented at AHA Scientific Sessions similarly found that social support (i.e., friends and family) moderated (weakened) the association between discrimination and adequate sleep duration, suggesting that social support is a resilience factor.

CALL TO ACTION:

Consider a stress-/trauma-informed approach to your clinical care and research agenda. Identifying and measuring stress and experiences of trauma as researchers will allow us to begin to work with our patients and communities to craft specific interventions to improve their health and well-being. Acknowledging trauma will allow us as clinicians to provide tailored care for our patients and their families.

References:

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697.

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):38-56.

- Meyer IH, Dietrich J, Schwartz S. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and suicide attempts in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1004-1006.

- Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J Behav Med. 2015;38(1):1-8.

- Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority Stress and Physical Health Among Sexual Minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(5):521-548.

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health socioeconomic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of health psychology. 1997;2(3):335-351.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.