Work life balance- Is This a Myth?

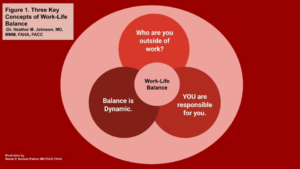

Work-life balance: for many in Cardiology it’s an elusive idea. Now, our worlds of work and “life outside of work” are even more blurred among Zoom meetings and facemasks. However, over the years, I have learned 3 important concepts (Figure 1) that has made work-life balance POSSIBLE, not just a myth.

Figure 1. Outlining the three key concepts of work-life balance.

Concept #1: Who are you outside of work?

As Cardiologists, researchers, educators, and team members we know the day, night, and weekend hours that define our careers. However, how do you describe yourself outside of work? Who are “you” after shedding the scrubs and white coat, away from the office, hospital, and lab? Beyond Cardiology, what are your interests? The answers to these questions help to define you and an important part of your life. When we lose our work-life balance, we are losing a part of ourselves.

To begin recapturing your interests, look at your calendar over the next month, and schedule small increments of time (just 5-10 minutes!) to reconnect with your personal interests (of course staying safely physically distant for now). These baby steps will move you closer to capturing the “life” in work-life balance.

Concept #2: “Balance” is dynamic.

How do you define “work-life balance”? Is it an equal distribution of time? Is it a certain quantity of time for specific activities?

Work-life balance is very similar to the field of Cardiology – it is constantly changing. For most people, work-life balance will not mean that there is “equal” or balanced time between work and personal life. Especially in Cardiology, our job usually engulfs the majority of hours in a week – clinical duties, grant deadlines, presentations, emails… and the list continues. However, for work-life balance, one of the goals is to “balance” the transition from work to “life outside of work”. This means your presence, attention, and focus should completely shift from work to your personal interests and interactions. Work-life balance is beyond physically leaving the job, but balancing the mental transition to fully shift away from work. It will take practice to avoid checking email or mulling over work. The amount of time between work and your personal life will remain dynamic; but the “balance” is your ability to commit your focus and attention to those precious personal moments, just as you do for work.

Concept #3: You are Responsible for You!

Cardiology requires you to constantly learn and practice to achieve and maintain competency. You are upholding a professional commitment. The same commitment is required to grasp work-life balance. You have to make a personal commitment to you!! It is not sufficient to just “wish for it”. We cannot expect anyone else to understand our needs or create our work-life balance.

To reframe this important concept, consider your self-care and work-life balance as critical as filling your car with gas (or charging your car): you cannot function without it! Your personal commitment has to be as strong as your professional commitment. No, it’s not easy, but it is possible. Some find it helpful to be accountable to a colleague or friend, check-in regularly (set a reminder) about small steps to promote work-life balance. We understand our responsibility to patients. Now, it’s time understand your responsibility to you!

During these uncertain times of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers are working longer hours and under even greater stress. It is normal to feel overwhelmed. Now, more than ever, it is important to find creative ways to focus on precious moments and commit to your well-being! Below are 5 tips to stay committed to yourself and safely connect with others:

- Take three minutes. Listen to your favorite song, dance while nobody’s watching, or take a few extra minutes in a hot shower. You do not need a long time to be kind to yourself.

- Join a Virtual group or class. Physical distancing and long work hours can be very isolating. Take advantage of the numerous virtual options to safely connect with others who have similar interests.

- Share and listen. Try moving beyond texting and talk on the phone. Commit to that moment, engage in the conversation and focus on listening. The human connection remains very powerful to strengthen our mind and body.

- Protect Your Time. I know it is easier said than done. However, learning to set boundaries is critical to sustain your commitment to work and participate in the joys of life.

- Be Kind to Your Body. Find time to sleep, eat healthy snacks, and participate in small amounts of physical activity. Mental health and physical health are equally important.

In summary, work-life balance is a journey, not a destination. Remember, that “balance” in work-life balance is dynamic – the amount of personal time will change, but your commitment and focus to that time should only grow.

About the Author:

Heather M. Johnson, MD, MMM, FAHA, FACC is a Cardiologist & Preventive Cardiologist at the Christine E. Lynn Women’s Health & Wellness Institute at Boca Raton Regional Hospital/Baptist Health South Florida.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”