In Santa Clara County, 75.6% of individuals (12 years+) are currently fully vaccinated. With cases of COVID-19 down and street traffic on the rise, it is clear that the “normal” I once dreamed of is quickly approaching. I am a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. In the laboratory, most restrictions are gone; there are no shifts, no distancing limits, and no limited room capacities. Yet, I still feel like I’m struggling. I still feel like I’m functioning at reduced productivity levels. While I completely acknowledge that my pre-pandemic lab hours were a bit crazy, and I should be okay with where I am, I want to get back to where I was. To help me with this, I spoke with an expert on productivity and stress, Dr. Steven Chan. Dr. Chan is on faculty at Stanford University, has taught students at the School of Business and School of Medicine, and has spoken and written on mental health at venues such as Google, NPR, and the American Psychiatric Association.

In Santa Clara County, 75.6% of individuals (12 years+) are currently fully vaccinated. With cases of COVID-19 down and street traffic on the rise, it is clear that the “normal” I once dreamed of is quickly approaching. I am a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. In the laboratory, most restrictions are gone; there are no shifts, no distancing limits, and no limited room capacities. Yet, I still feel like I’m struggling. I still feel like I’m functioning at reduced productivity levels. While I completely acknowledge that my pre-pandemic lab hours were a bit crazy, and I should be okay with where I am, I want to get back to where I was. To help me with this, I spoke with an expert on productivity and stress, Dr. Steven Chan. Dr. Chan is on faculty at Stanford University, has taught students at the School of Business and School of Medicine, and has spoken and written on mental health at venues such as Google, NPR, and the American Psychiatric Association.

Please describe yourself and your pursuit of improved productivity?

I am currently a medical director at a busy service in Northern California. I also work on healthcare technology, focusing on projects in the area of digital mental health. I am interested in the application of mental health on technology, and how this can improve people’s lives.

Productivity has always been a lifelong pursuit for me. Growing up, I was always very busy with extracurriculars: music, martial arts, exam prep, newspaper, the list goes on. There was always a lot to do that required a lot of time to excel at it. Then, when I went to college, the pattern continued. Same thing again with work life.

Over time, I’ve realized that it’s not only important to understand how the right tools can help you get more done, but also how to identify the right work to tackle.

What do you mean by “right work?” How do you decide where to invest your time?

When I am approached with a new opportunity, I choose to take on new projects based on three criteria:

- Enjoyment. Is this something I enjoy doing? Do I have good feelings?

- Skills. Am I good at this task? Or, is this an opportunity to learn new skills?

- Returns. Is there a return on investment (ROI)? This return doesn’t have to be purely financial and monetary; it could be rich in social connections. It could be valuable for your organization and yourself.

Ideally, new projects would have all three. Otherwise, a project would be imbalanced. Take enjoyment, for example. If a project involved evaluating pizza, well, I enjoy eating pizza, but it doesn’t take much skill and it’s unlikely someone would pay me to eat pizza.

Time is your most precious commodity. In careers such as medicine and science, there is an abundance of work and projects. Choose to do things that you enjoy, you are skilled at, and are worth your time.

I find myself saying “yes” to a lot of things — and I get overwhelmed! How do you say “no”? How do you deal with feelings that you are passing up on an opportunity?

Anytime you say “yes” to something, you have to be aware that you are saying “no” to other opportunities.

When people think about the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) or the fear of disappointing others, they think that they are permanently closing the door on an opportunity. This is simply not true.

In the past, I used to say “yes” to a lot of opportunities because I didn’t know where to best invest my time. The key to choosing good opportunities is to first have a good bird’s eye view of the opportunities out there. This requires some work and reflection. Know all the things going on in your life, identify your goals and values, and then get to know all the opportunities available to you. And after doing all this, make commitments using the three criteria we discussed earlier.

One final point, have regularly-scheduled reviews of your commitments. Do a weekly assessment, think about all the things you want to accomplish in a week, a month, and a year. Then adjust your commitments to ensure your maximal efforts line up with your long-term goals.

I feel like I am always short on time. What are the top 3 things I can do to help me with my productivity?

There are a lot of calendar hacks and to-do tips out there. But having the right mindset is critical before taking on new apps and new techniques:

Keep experimenting. There is no one perfect solution or single app that will organize your life. However, there is a whole community out there devoted to time optimization and productivity. These solutions and best practices evolve and change as you move through life. For example, when I transitioned from medical school to the work world, I quickly realized that it was no longer sufficient to write things down on paper. So, I turned to automated calendars. Now I use Busycal and Google Calendar, with Outlook at my main job.

Do reflections and get to know yourself. You can’t understand what you are good at, what you enjoy, and what you want in life without self-reflection. I remember going through the motions of classes and training, and it wasn’t until I got to stop and reflect that I truly was able to ensure a better balance between work and self-care.

Know your energy levels. For example, I know that I can’t get anything done in the evenings because I’m exhausted. When I was in medical school, I used to beat myself up over this because I felt the need to study every evening. But, now I know that I have much more energy in the mornings and commit more time to getting work done then. In addition to knowing when you work best, you can hack your energy levels by optimizing caffeine intake and exercise to boost energy levels when required.

Lastly, adjust your surroundings. Equip yourself with the right technology — fast, reliable computers; fast, reliable internet; and fast, reliable smartphones. Surround yourself with the right people to maximize your output. The energy levels of your peers matter. Establishing an environment with minimal toxicity and drama is essential. Do this at work, at home, and in your relationships.

How do you quiet that inner critic? How do you deal with feelings that you are not doing enough or not making enough progress?

Recontextualize or reframe this to determine if this feeling of inadequacy is true. Again, make time for reflection. List out all your projects and accomplishments, and then assess if you really are not doing enough. Ideally, a therapist, counselor, or coach can help you with this reflection — but there are so many worksheets and courses on the internet to guide you in doing the same.

Every year, instead of making New Year’s resolutions, I assess all the things I have done and the things I have failed at. Yes, I keep a failure list, which sounds horrifying. I can’t tell you how many internships, jobs, relationships, and projects of mine have failed! But, I feel having a list of failures is an important step in beating perfectionism. A failure isn’t a bad thing. It means you are experimenting! Experimentation is good, leads to growth, and helps you learn. While failure can be a brutal blow to self-esteem, we need to fail in life. Failure provides feedback. In fact, if we have repeated failures, this tells us that we need to make significant changes in what we’re doing!

Are there resources that you would suggest to help with improved productivity and mental health?

Take a look at articles published in the business world regarding productivity and human performance. In business, people want to get the most out of their precious resources: time, money, and human resources. Read up on project management techniques, as these will help you run efficient labs, manage clinical teams, and even run research papers and grant-writing projects.

Where can you find these? A major resource is a library or even your HR team: many universities and workplaces have access to LinkedIn Learning and Skillshare. And, Mental Power Hacks — the website I run — plus my social media feeds at @mpowerhacks, also feature a lot of these techniques. I know this is a lot, and you won’t conquer it all in one sitting, but incorporate this learning in your routines to build these skills over time.

Thank you so much for these! In our next blog entry, we’ll talk about how to improve your productivity by managing relationships in both work and social life.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

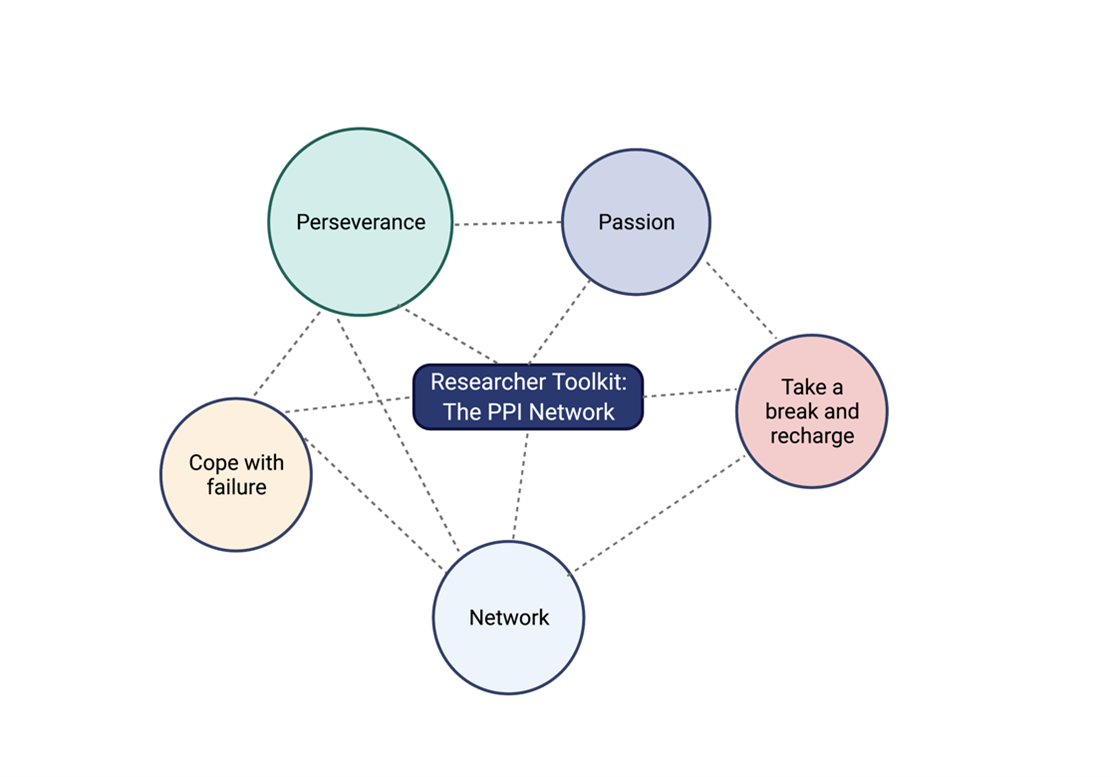

I had the pleasure of having a one-on-one virtual meet-up with Mabruka Alfaidi MD, PhD who won the ATVB Investigator in Training Award Competition during last year’s Vascular Discovery 2021 meeting based on her fascinating work on endothelial cells and IL-1b signaling pathway as well as her active involvement with the research community. We discussed her career path and her future projects which we couldn’t do without also going over the many hurdles that come our way as researchers. I decided to summarize the main themes that we tackled in a researcher’s toolkit which encompasses key ingredients to sustain a career in research: The PPI network.

I had the pleasure of having a one-on-one virtual meet-up with Mabruka Alfaidi MD, PhD who won the ATVB Investigator in Training Award Competition during last year’s Vascular Discovery 2021 meeting based on her fascinating work on endothelial cells and IL-1b signaling pathway as well as her active involvement with the research community. We discussed her career path and her future projects which we couldn’t do without also going over the many hurdles that come our way as researchers. I decided to summarize the main themes that we tackled in a researcher’s toolkit which encompasses key ingredients to sustain a career in research: The PPI network.

In Santa Clara County, 75.6% of individuals (12 years+) are currently fully vaccinated. With cases of COVID-19 down and street traffic on the rise, it is clear that the “normal” I once dreamed of is quickly approaching. I am a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. In the laboratory, most restrictions are gone; there are no shifts, no distancing limits, and no limited room capacities. Yet, I still feel like I’m struggling. I still feel like I’m functioning at reduced productivity levels. While I completely acknowledge that my pre-pandemic lab hours were a bit crazy, and I should be okay with where I am, I want to get back to where I was. To help me with this, I spoke with an expert on productivity and stress,

In Santa Clara County, 75.6% of individuals (12 years+) are currently fully vaccinated. With cases of COVID-19 down and street traffic on the rise, it is clear that the “normal” I once dreamed of is quickly approaching. I am a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. In the laboratory, most restrictions are gone; there are no shifts, no distancing limits, and no limited room capacities. Yet, I still feel like I’m struggling. I still feel like I’m functioning at reduced productivity levels. While I completely acknowledge that my pre-pandemic lab hours were a bit crazy, and I should be okay with where I am, I want to get back to where I was. To help me with this, I spoke with an expert on productivity and stress,  Please describe yourself and your prior training.

Please describe yourself and your prior training.