Tardiness Of Science Leads To Public Skepticism

AHA17 introduced the new and controversial blood pressure measurement guidelines during its annual conference in Anaheim, CA, raising skepticism among the masses. However, before I get into what the new recommendations are, let’s review how blood pressure measurements were initially established. Historically, over the last century blood pressure was unstudied by the scientific and clinical communities. The realization of the importance of blood pressure to health was first observed over 4,000 years ago by Huang-Ti, the yellow Emperor of China, with the discovery that people who ate too much salt had “harder” pulses and subsequently suffered from more strokes. Precise blood pressure measurements did not come about until Samuel Siegfried Ritter von Basch developed the sphygmomanometer for clinical use in 1880. The concept of hypertension, previously termed hyperpiesia, did not make an appearance until 1896 with the introduction of auscultating Korotkoff sounds (the sounds heard through the stethoscope when the artery is occluded by the sphygmomanometer and pressure released slowly). Having this new technology revolutionized the means of measuring blood pressure.

As the technique for blood pressure measurement developed over the years, so did the basis for the clinical diagnosis of hypertension. However, there was still debate as to how to treat it. In 1949, Charles Friedberg suggested in the textbook “Diseases of the Heart” that mild ‘benign’ hypertension (210/100 mmHg) should not be treated. During this era, blood pressure treatment was so controversial that the common thought was, ‘the greatest danger to a person with high blood pressure was knowing, because some fool will try to reduce it’. To put that statement into perspective, this was still a time when people were bled by leeches to reduce blood pressure leading to increased incidences of death due to the treatment regimen. The next era of treatment was to do nothing. Researchers started to explore the idea that high blood pressure was a compensatory mechanism, which should not be tampered even if clinicians were certain it could be controlled. This line of thinking lead to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality due to the prevalence of cardiovascular disease caused in part by the untreated blood pressure. With this revelation, high blood pressure treatment and diagnosis was forever changed, starting with the level that is considered to be high (140/80 mmHg).

The first clinical breakthrough in hypertension treatment was the discovery of diuretics. The addition of this drug class reduced strokes and ischemic heart disease by ~50% between 1972 and 1994. Once beta blockers came on the scene for the use of angina, researchers found, by accident none the less, that they additionally lowered blood pressure. How about that?! With research advancing in the area of hypertension, there have been several drugs to come on the market to lower blood pressure including calcium channel blockers and sartan drugs. These medications have had enormous benefit in reducing cardiovascular disease.

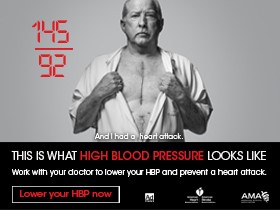

This leads us to the new classifications of normal and high blood pressure. At AHA17, the new range for defining systolic/diastolic blood pressure in patients is as follows: normal (90-119 mmHg/60-79 mmHg), prehypertension stages I (120-139 mmHg /81-89 mmHg), and stage II (≥160 mmHg/ ≥100 mmHg), as well as isolated systolic hypertension (≥140 mmHg /<90 mmHg). These measurements are based on the average seated, relaxed blood pressure reading obtained over two or more office visits. Although these are the new recommendations, these numbers are interpreted in conjunction with the clinician’s understanding of the patient’s history. For example, if a patient has a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg coupled with other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2 or kidney disease, then this might require more aggressive treatment than a patient with no underlying disease. Physicians will furthermore take into account a patient’s age and overall health when making the decision of how or when to medicate. For example, a patient with resistant hypertension (blood pressure that fails to be reduced with appropriate antihypertensive medicine) may require additional drugs. Because we know that hypertension can be a consequence of both environmental and behavioral factors, AHA still suggests that we adopt a healthy lifestyle that includes a diet focused on heart health, as well as incorporating exercise into our activities of daily living.

There has been some controversy in the news and on social media about these changes. Whether these changes are in the best interest of the general population or in the interest of those who stand to gain from more people having hypertension. This could indeed lead to more patients taking medicine, and consequently more people having higher insurance premiums. It could also lead to more income for primary physicians and pharmaceutical companies. With these things being considered, none of them are more important than one’s health! There are things that cannot be controlled, such as age, sex and genetics, but that does not change the fact that it is the individual’s responsibility to live a healthy lifestyle and take control of their health care. This starts by knowing your risk, eating healthy, and regular exercise.

I know this is a lot of information to take in, but the real message here is: (1) do not allow social media to dictate your health. There are going to be a lot of things said by all types of people, but the best resource is your clinical staff. (2) Yes, regular medical appointments are still necessary to determine whether blood pressure should be treated or how it should be treated. (3) Although the blood pressure scale has changed slightly to incorporate more hypertensive stages, the definition of a healthy blood pressure has not really been modified. Experts (clinicians and scientist) are at odds as to whether patients over 70 years of age should be treated with additional medicines in order to reduce blood pressure. To add more antihypertensive drugs to a patient in such a vulnerable age group could lead to increased side effects such as hypotension, dizziness, increased prevalence of renal failure, enhanced fall risk, and alterations to activities of daily living. There are guidelines published in the JAMA for more information on the recommendations for the geriatric population. Science takes time. It takes a lot of studying to get the results that change the way experts view our clinical practice. It may seem to the general public that these data are tardy, but they are, in my opinion, timely.

I am interested in knowing more about the benefits of the new blood pressure scale and how this will tangibly change the occurrence of cardiovascular disease, cardiorenal disease, and chronic renal disease. I also wonder what questions will now arise in the general population regarding these new developments.

Anberitha Matthews, PhD is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis TN. She is living a dream by researching vascular injury as it pertains to oxidative stress, volunteers with the Mississippi State University Alumni Association, serves as Chapter President and does consulting work with regard to scientific editing.