Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment And Dementia And Risk Factors and Prevention

Dr. Rebecca Gottesman presented on Thursday during the Stroke Conference of 2021. She addressed the past, present, and future related to vascular dementia, mixed dementia, early stroke recovery, and precision medicine.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30784556/

In the past, the definition of post-stroke dementia was not necessarily uniform. She explains this is related to the term vascular dementia being sort of “tricky”. When classifying dementia you should consider, when you look, where you look, and whom you are looking at?

Many people can have dementia prior to having the stroke, this important when reviewing the prevalence rates after the stroke. Nearly 10% has dementia prior to stroke onset (1).

Dr. Gottesman highlights the need to review mixed pathologies for vascular dementia. The trajectories of onset and recovery vary between people. There can be a decline in cognition, followed by a recovery, then a further decline or an improvement. The Individual-level risk is important in post-stroke dementia.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017319

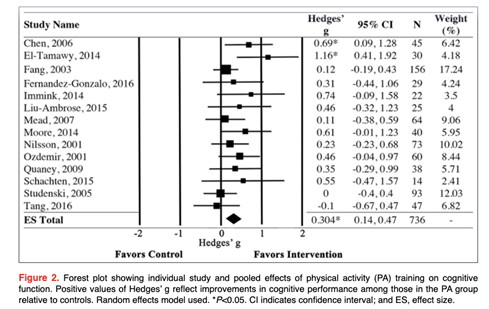

Dr. Gottesman shared that the same stroke does not affect the person the same way (not every stroke leads to the same outcome). The individual risk profile will help individualize treatments and allow for more precision in medicine. She acknowledges that it is difficult to identify everyone who may have a stroke before they have an actual stroke. The meta-analysis from Oberlin highlights leisure activity as a potential way to reduce post-stroke dementia (2). Near the end of the presentation, Dr. Gottesman suggests we consider the following questions:

1) How do you consider aphasia and other cognitive deficits from the stroke?

2) How much time should pass after the stroke before you call it “dementia”?

3) How do you characterize dementia?

4) How do you characterize the dementia subtype?

5) How might future studies improve post-stroke cognitive outcomes?

We should consider the different prevention approaches due to the number of the different pathologies related to post-stroke dementia.

References

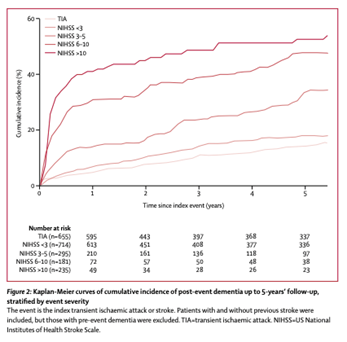

- Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Incidence and prevalence of dementia associated with transient ischaemic attack and stroke: analysis of the population-based Oxford Vascular Study. The Lancet Neurology. 2019 Mar 1;18(3):248–58.

- Oberlin LE, Waiwood AM, Cumming TB, Marsland AL, Bernhardt J, Erickson KI. Effects of Physical Activity on Poststroke Cognitive Function: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Stroke. 2017 Nov;48(11):3093–100.

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”