Cardiovascular risk assessment is a process, not just a calculation! This year, I was very pleased to attend the 2018 guidelines for cholesterol management at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions – Chicago 2018. I highly recommend that you check the guidelines as there are many changes that may impact your daily practice. Here, I’m summarizing the late breaking trials that were presented at the last AHA and encouraging you to join us at the next AHA Scientific Sessions meeting – Philadelphia 2019.

Critical Questions in Cardiovascular Prevention:

The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL): Principal Results for Vitamin D and Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer.

- RESULTS: Major CVD events and total invasive cancer not significantly reduced by Omega-3 or vitamin D3. Omega-3 significantly reduced total MI, especially in African Americans and those with lower baseline fish intake.

The Primary Results of the REDUCE-IT Trial.

- RESULTS: High-dose icosapent ethyl vs. placebo in at-risk patients significantly reduced the composite CVD endpoint: risk of CV death, MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, and unstable angina.

Ezetimibe in Prevention of Cerebro- and Cardiovascular Events in Middle- to High-Risk, Elderly (75 Years Old or Over) Patients with Elevated LDL-Cholesterol: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled, Open-Label Trial.

- RESULTS: Ezetimibe monotherapy + diet counselling vs diet counselling alone for primary prevention (elevated LDL-C; no history of CAD) in an over-75 y/o Japanese population significantly prevented cerebral and cardiovascular events.

Cost-Effectiveness of Alirocumab Based on Evidence from a Large Multinational Outcome Trial: The ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Economics Study.

- RESULTS: For the patients in the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial (post-ACS and LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL), alirocumab was found to be cost effective.

Novel Approaches to CV Prevention:

The Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events (DECLARE)-TIMI 58 Trial.

- RESULTS: Dapagliflozin compared to placebo in patients with T2DM was safe, reduced the composite of CV death or hospitalization for heart failure, but did not impact MACE.

The Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT): Low Dose Methotrexate for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Events.

- RESULTS: Low dose methotrexate compared to placebo in patients with prior MI or multivessel CVD and either type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome, did not reduce inflammatory markers, and CV events weren’t lower than placebo.

Safety and Efficacy of AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx to Lower Lipoprotein(a) Levels in Patients with Established Cardiovascular Disease: A Phase 2 Dose-Ranging Trial.

- RESULTS: Dose-dependent lowering of Lp(a) levels by AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx were seen in patients with pre-existing CV disease or PAD in this phase 2 trial

Harnessing Technology and Improving Systems for Global Health:

Effects of a Multifaceted Intervention to Narrow the Evidence-Based Gap in the Treatment of High Cardiovascular Risk Patients: The BRIDGE CV Prevention Cluster Randomized Trial.

- RESULTS: Adherence to evidence-based therapies (antiplatelets, statins and ACE inhibitors) for high CV risk Brazilian patients was improved with use of a multifaceted quality improvement educational intervention vs routine practice.

Alert-Based Computerized Decision Support to Increase Anticoagulation Prescription Prevents Stroke and Myocardial Infarction in High-Risk Hospitalized Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: A Randomized, Controlled Trial.

- RESULTS: Alert-based computerized decision support in high-risk hospitalized AF patients increased prescribing of anticoagulation for stroke prevention and reduced major adverse cardiovascular events, MI and stroke.

Efficacy of Electronic Clinical Decision Support in Atrial Fibrillation: Results of the Integrated Management Program Advancing Community Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (IMPACT-AF).

- RESULTS: An online, evidence-based computer decision support system did not significantly affect the number of patients experiencing the unplanned cardiovascular hospitalization and/or AF-related emergency room visit at 12 months.

Preserving Brain & Heart in Acute Care Cardiology:

Pre-Hospital Resuscitation Intra-Arrest Cooling Effectiveness Survival Study – The Princess Trial.

- RESULTS: Survival with good neurologic outcome 90 days after cardiac arrest was not statistically different for pre-hospital trans-nasal evaporative intra-arrest cooling compared to standard care.

Early Goal-Directed Hemodynamic Optimization in Comatose Survivors After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: The Neuroprotect Trial.

- RESULTS: A higher mean arterial pressure (MAP) in the ICU during the first 36 hours after cardiac arrest improved cerebral perfusion and oxygenation but did not decrease anoxic brain damage or improve functional outcome compared to the lower MAP target of 65mmHg.

A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel Group, Multicenter Clinical Trial of Low-Dose Adjunctive Alteplase During Primary PCI (T-TIME).

- RESULTS: Compared to placebo, microvascular obstruction was not different for low-dose alteplase during primary PCI for acute STEMI.

Optimal Timing of Intervention in Non St-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes Without Pretreatment.

- RESULTS: In not pre-treated intermediate and high-risk NSTEACS patients, a very early (<2 hours) invasive intervention strategy compared to a delayed one (≥12-72 hours) was highly significant for reduction in CV death or recurrent ischemic events @ 30 days.

Mechanically Unloading the Left Ventricular and Delaying Reperfusion in Patients with Anterior ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The Door to Unload Pilot Trial.

- RESULTS: In patients with anterior STEMI, mechanical unloading of the left ventricle followed by either immediate vs delayed reperfusion found no difference in MACCE between the two groups and no increase in 30-day infarct size in the delayed group.

Hot News in HF:

Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: Primary Results of the PIONEER-HF Randomized Controlled Trial.

- RESULTS: This comparison of sacubitril/valsartan to enalapril in patients hospitalized with HFrEF found that sacubitril/valsartan resulted in significantly more reduction in NT-proBNP levels.

Withdrawal of Pharmacological Heart Failure Therapy in Recovered Dilated Cardiomyopathy – A Randomised Controlled Trial (TRED-HF).

- RESULTS: Withdrawal of therapy in ‘recovered’ dilated cardiomyopathy patients resulted in relapse for 40% compared to 0% relapse for those who remained on therapy. “Recovered’ patents are in remission.

Effects of Rivaroxaban on Thrombotic Events in Heart Failure Patients with Coronary Disease and Sinus Rhythm.

- RESULTS: Low-dose rivaroxaban use in HF significantly reduced the risk for thromboembolic events in the COMMANDER HF trial population.

EMPA-HEART Cardiolink-6 Trial: A Randomized Trial Evaluating the Effect of Empagliflozin on Left Ventricular Structure, Function and Biomarkers in People with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) and Coronary Heart Disease.

- RESULTS: In patients with T2DM and stable CAD, LV mass was significantly reduced by empagliflozin compared to placebo.

Coronary Revascularization:

Endoscopic Vein Harvest for Coronary Bypass Surgery in a Randomized Multicenter Trial with Long-Term Follow-Up.

- RESULTS: Late findings for endoscopic vs open SVG harvesting for CABG found MACE rates were similar @ 2.7 years’ follow-up.

Long-Term Survival Following Multivessel Revascularization in Patients with Diabetes: The FREEDOM Follow-On Study.

- RESULTS: At the 8-year FREEDOM trial follow-up, CABG showed lower rate of all-cause mortality over 8-year follow-up compared to PCI in patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease.

TiCAB: A Randomized, Double-Blind Study of Ticagrelor versus Aspirin in Patients Undergoing Coronary Bypass Surgery.

- RESULTS: In patients having CABG, major CV events and bleeding rates were not significantly reduced with ticagrelor monotherapy compared to aspirin.

Ten-Year Clinical Outcomes After Coronary Drug-Eluting Stents with Biodegradable or Permanent Polymer Coating: Results from the Randomized ISAR-TEST 4 Trial.

- RESULTS: 10-year CV outcomes were superior for three limus-eluting stents with different polymer coatings compared to early-generation stents.

Intramyocardial Injection of Mesenchymal Precursor Cells in Left Ventricular Assist Device Recipients: Impact on Myocardial Recovery and Morbidity.

- RESULTS: Successful temporary LVAD weans over 6 months and 1-year mortality were similar for intramyocardial mesenchymal precursor cell injection vs sham injection.

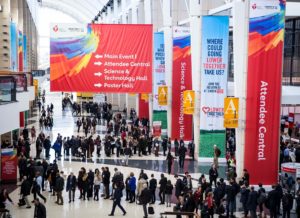

At my first two AHA Scientific Sessions, I sat in the Main Event Hall, shoulder-to-shoulder with my co-fellows, eagerly awaiting the results of the Late Breaking Clinical Trials and guideline updates. I remember whispers cascading across the room after the presentation of NEAT-HFpEF in 2015 and the hundreds of cellphones in the air snapping pictures of the hypertension guideline release in 2017. This year as an AHA Early Career Blogger, I learned the results of the Late Breaking Clinical Trials with other news writers at embargoed media briefings. These intimate press conferences are routinely offered to health care journalists at major medical meetings and by top medical journals. Members of the media receive early access to manuscripts and data and discuss trial findings with investigators and outside experts with the understanding that nothing should be published until after trial results are publicly released. Generally, media pieces are published very soon after the embargo is lifted. At my first embargoed briefing, I heard one reporter’s question that has spurred me to imagine a new, more inclusive future for scientific meetings.

At my first two AHA Scientific Sessions, I sat in the Main Event Hall, shoulder-to-shoulder with my co-fellows, eagerly awaiting the results of the Late Breaking Clinical Trials and guideline updates. I remember whispers cascading across the room after the presentation of NEAT-HFpEF in 2015 and the hundreds of cellphones in the air snapping pictures of the hypertension guideline release in 2017. This year as an AHA Early Career Blogger, I learned the results of the Late Breaking Clinical Trials with other news writers at embargoed media briefings. These intimate press conferences are routinely offered to health care journalists at major medical meetings and by top medical journals. Members of the media receive early access to manuscripts and data and discuss trial findings with investigators and outside experts with the understanding that nothing should be published until after trial results are publicly released. Generally, media pieces are published very soon after the embargo is lifted. At my first embargoed briefing, I heard one reporter’s question that has spurred me to imagine a new, more inclusive future for scientific meetings. On Sunday of Sessions, I joined other health care reporters for the VITAL and REDUCE-IT presentations. In VITAL, 1 gram/day of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (containing 460 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and 380 mg of docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) was not effective for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in healthy middle-aged adults. In REDUCE-IT, icosapent ethyl (a purified EPA) at a dose of 2 grams twice daily reduced cardiovascular events among patients at risk for or with known cardiovascular disease and with high triglycerides already on statin therapy with good LDL-C control. After both trials were presented, one news writer probed the primary investigators’ thoughts on communicating these results to patients. The reporter wondered if the trials could be interpreted as sending mixed messages about the cardiovascular benefits of omega-3 fatty acids to the general public. Both trials’ primary investigators acknowledged this concern and systematically reviewed the differences in drug composition, patient populations, and study goals that, in their estimation, led to the outcomes. Multiple panelists implored the journalists to integrate these differences into their stories with hopes that consumers and potential patients would be able to understand the distinctions on their own.

On Sunday of Sessions, I joined other health care reporters for the VITAL and REDUCE-IT presentations. In VITAL, 1 gram/day of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (containing 460 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and 380 mg of docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) was not effective for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in healthy middle-aged adults. In REDUCE-IT, icosapent ethyl (a purified EPA) at a dose of 2 grams twice daily reduced cardiovascular events among patients at risk for or with known cardiovascular disease and with high triglycerides already on statin therapy with good LDL-C control. After both trials were presented, one news writer probed the primary investigators’ thoughts on communicating these results to patients. The reporter wondered if the trials could be interpreted as sending mixed messages about the cardiovascular benefits of omega-3 fatty acids to the general public. Both trials’ primary investigators acknowledged this concern and systematically reviewed the differences in drug composition, patient populations, and study goals that, in their estimation, led to the outcomes. Multiple panelists implored the journalists to integrate these differences into their stories with hopes that consumers and potential patients would be able to understand the distinctions on their own. After the briefing, I walked to the Main Event Hall to re-experience the Late Breaking Clinical Trials and thought about how we translate these breakthroughs, frequently announced at scientific meetings, to the public and our patients. Recent data suggest that the use of social media at cardiovascular conferences, a key approach to broadcasting late-breaking scientific developments, is rapidly growing. At these meetings, physicians comprise the largest group of Tweeters and compose nearly half of all tweets.1 Identifying the full scope of our social media audience, though, is more elusive. Ensuring veracity in scientific communication has become progressively challenging as the attitudes and tools to perpetuate misinformation have spread. We know that across multiple information domains, false news spreads faster, farther, and deeper than the truth.2 Just this week, Dictionary.com chose “misinformation” as the 2018 word of the year.3 Clinicians and scientists are now especially vulnerable to this insidious erosion of public trust.

After the briefing, I walked to the Main Event Hall to re-experience the Late Breaking Clinical Trials and thought about how we translate these breakthroughs, frequently announced at scientific meetings, to the public and our patients. Recent data suggest that the use of social media at cardiovascular conferences, a key approach to broadcasting late-breaking scientific developments, is rapidly growing. At these meetings, physicians comprise the largest group of Tweeters and compose nearly half of all tweets.1 Identifying the full scope of our social media audience, though, is more elusive. Ensuring veracity in scientific communication has become progressively challenging as the attitudes and tools to perpetuate misinformation have spread. We know that across multiple information domains, false news spreads faster, farther, and deeper than the truth.2 Just this week, Dictionary.com chose “misinformation” as the 2018 word of the year.3 Clinicians and scientists are now especially vulnerable to this insidious erosion of public trust. How do we combat the propagation of falsehood while encouraging this new democratization of science? I have thought about how the importance of trust was so admirably exemplified in a recent study of blood pressure reduction in black barbershops.4 What if we could leverage our meetings to spread science to where our patients are and with trusted people delivering the message? The AHA has recognized this opportunity and does have programs in place, like “Students at Sessions”, to share Scientific Sessions with non-medical communities.5 Can we imagine a future state of Scientific Sessions where internationally recognized clinicians and scientists deliver a talk at a barbershop or civic center in the host city, where community leaders are invited to participate in panels and plenaries, where large scale cardiovascular risk screenings happen just outside our conference center doors?

How do we combat the propagation of falsehood while encouraging this new democratization of science? I have thought about how the importance of trust was so admirably exemplified in a recent study of blood pressure reduction in black barbershops.4 What if we could leverage our meetings to spread science to where our patients are and with trusted people delivering the message? The AHA has recognized this opportunity and does have programs in place, like “Students at Sessions”, to share Scientific Sessions with non-medical communities.5 Can we imagine a future state of Scientific Sessions where internationally recognized clinicians and scientists deliver a talk at a barbershop or civic center in the host city, where community leaders are invited to participate in panels and plenaries, where large scale cardiovascular risk screenings happen just outside our conference center doors?