Introduction

Despite advances in health care in the United States (US) maternal morbidity and morbidity remains significantly higher in the US relative to other developed nations with a reported maternal mortality of 14 per 100,000 live births in 20151. Unfortunately, maternal morbidity and mortality rate has steadily increased over the last 2 decades2. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) implemented the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. The CDC defines a pregnancy-related death as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of a pregnancy – regardless of the outcome, duration or site of the pregnancy–from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes2. Although the maternal morbidity and mortality rate declined in the 20th century, recent statistics have shown that this rate has increased more than 2 fold as the number of reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States steadily increased from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 17.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015. More recent date has suggested that this rate is even higher at 26.4 per 100,000 live births3. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounts for approximately a third of pregnancy related deaths and is the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality2. According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) acquired heart disease is thought to be the cause for the rising cardiovascular mortality in women with an increasing number of mothers entering pregnancy with a greater burden of common risk factors for CVD such as age, obesity, diabetes and hypertension2,3.

Disparities in Outcomes

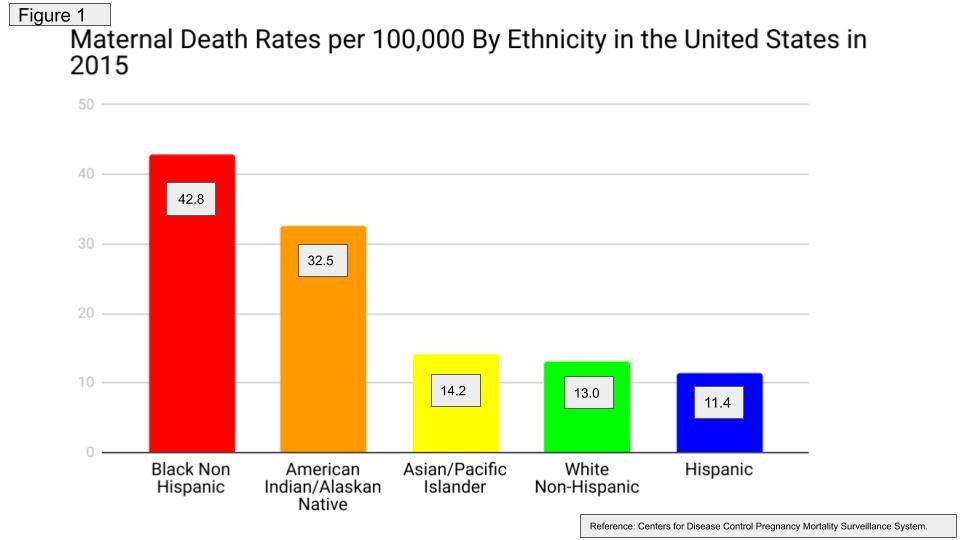

There are also significant racial and ethnic disparities seen in maternal morbidity and mortality rates in the US with Black women having a greater than 3 fold higher rate compared to White, non-Hispanic women (42.8 per 100,000 vs. 13 per 100,000 live births)2. The lowest maternal morbidity and mortality rate is seen in Hispanic women with a rate of 11.4 per 100000 live births. This rate progressively increases with White Non Hispanic women having a rate of 13.0 per 100,000 live births followed by 14.2 per 100,000 in Asians/Pacific Islander, 32.5 in American Indian Alaskan Native, and is highest in Black Non-Hispanic Women of 42.5 per 100,000 live births2 Figure 1.

The cause of this disparity is multifold and may also be related to a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors such as obesity and hypertension in Black non-Hispanic women4. There may also be limited access to adequate postpartum care in this patient population. There has been some action taken by ACOG with regards to providing recommendations for addressing these disparities5,6. However, there is a lot of work left to be done in resolving these inequities in maternal healthcare.

Role of the Cardiologist

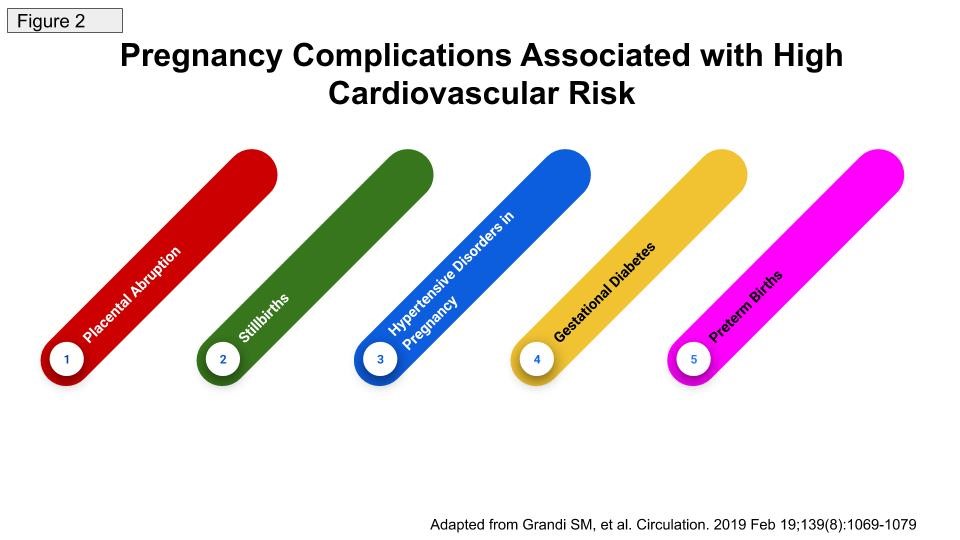

It is vital that mothers who are at increased risk for CVD or have established CVD be referred to a Cardiologist for cardiovascular assessment and management in the early postpartum period. Therefore, raising the awareness amongst the Obstetrics and Gynecology community of this necessity of cardiovascular care in these women is important. Additionally, for us in the Cardiology community it is important to recognize these female patients when they present to us for the first time for care. Their presentation may be in the antepartum or postpartum period. In the antepartum period it is vital for us to be able to differentiate pathologic cardiovascular signs and symptoms from the physiologic cardiovascular changes related to pregnancy. It is also important that if these women present to us in the antepartum or postpartum period that they have an adequate assessment of their cardiovascular risk. Key historical features to obtain includes a thorough obstetrics history as there are several pieces of the obstetric history that may indicate a higher cardiovascular risk such as preterm deliveries, pre-eclampsia and frequent first trimester miscarriages. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in Circulation in 2018 by Grandi S, et al analyzed 84 studies that included more than 28 million women and had indicated that women with placental abruption and stillbirth in addition to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus, and preterm birth are at increased risk of future cardiovascular disease7 Figure 2. In addition to an obstetrics history, a family history of heart disease particularly premature heart disease is also important. These women should also be assessed for common CVD risk factors such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking and a sedentary lifestyle. These risk factors should be appropriately and intensively managed through a combination of therapeutic lifestyle changes and medications where appropriate.

In the prepartum period women intending to become pregnant should also be screened with regards to their CVD risk assessment and these risk factors should be appropriately managed to improve their overall CVD health prior to becoming pregnant. This is especially so as pregnancy could be viewed as nature’s stress test and the more cardiovascularly healthy women are when they conceive the more likely they will have better cardiovascular outcomes in the postpartum period.

In unique cases of women with Congenital Heart disease, it is imperative that these patients are seen by an Adult Cardiologist with expertise in Adult Congenital heart disease before considering pregnancy as there may be cases where women with certain Adult Congenital heart diseases or pathology such as Eisenmenger’s syndrome should be advised to avoid pregnancy. Additionally, there may be cases where therapies or procedures may have to be considered prior to becoming pregnant such as women with Marfan’s syndrome with significant aortic root dilation.

Solutions to the Problem

The rise in maternal morbidity and mortality in the US has been attributed to acquired CVD1 and is therefore preventable. In order to address this problem the following should be considered:

- Recognition and management of CVD risk factors in the prenatal Period

- Appropriate cardiovascular assessment in the prenatal period for women with congenital heart disease to determine if pregnancy is contraindicated and if not contraindicated to determine suitable follow up of these women in the ante and postpartum period. Appropriate delivery plan should be outlined in an appropriate tertiary high Obstetrics risk center with appropriate cardiovascular and neonatal services available.

- Adequate cardiovascular follow up during the pregnancy and postpartum period for women with an intermediate as well as a high CVD risk.

- A multidisciplinary Pregnancy Heart Team approach is important for women with intermediate and high CVD risk in the antepartum and postpartum period.

- Early postpartum period cardiovascular assessment is important in the first 1-2 weeks post delivery for women with high CVD risk features such as women with placental abruption and stillbirth in addition to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus, and preterm births.

- Women with high CVD risk should have long term cardiovascular care not only in the first year postpartum but these women will likely require long term cardiovascular follow up even beyond a year to improve their lifelong cardiovascular risk.

- Removal of barriers to access to appropriate prenatal, antepartum and postpartum cardiovascular care is important for all women regardless of race or ethnicity.

- Raising awareness of the elevated maternal morbidity and mortality risk predominantly due to CVD is important in both the Cardiovascular and Obstetric Gynecology medical community so that as providers we can deliver the best possible care to these patients to improve their outcomes.

Future Directions

With the increasing maternal morbidity and mortality in the US that has been attributed to CVD there is a role for increased collaboration between the Cardiologist and the Obstetrician with regards to a Pregnancy Heart Team. The role of this team is vital in improving CVD outcomes in the antepartum and postpartum period for these women. Hopefully the research collaborative called the Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy: Expectations (HOPE) for Mom and Baby Registry which aims to address key clinical questions surrounding the preconception period, antenatal care, delivery planning and outcomes, and long-term postpartum care and outcomes of women will help to address the knowledge gaps and disparities in the care of women with heart disease in pregnancy8.

There is also a need for greater risk prediction tools with regards to assessing CVD risk in the prenatal, antenatal and postnatal period. The recently concluded Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPEG II) study indicated that there were 10 predictors that could be utilized to assess maternal CVD risk9. These 10 predictors include:

- 5 general predictors;

- Prior cardiac events or arrhythmias (3 points)

- Poor functional class or cyanosis (3 points)

- High-risk valve disease/left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (3 points)

- Systemic ventricular dysfunction (2 points)

- No prior cardiac interventions (1 point)

- 4 lesion-specific predictors:

- Mechanical valves (2 points)

- High-risk aortopathies (2 points)

- Pulmonary hypertension (2 points)

- Coronary artery disease (2 points)

- 1 delivery of care predictor (late pregnancy assessment) (1 point)

Patients with a higher CARPREG II score had a higher incidence of adverse cardiac events in pregnancy.

It is hopeful that these new initiatives will assist providers in improving their ability to appropriately risk stratify women in the prenatal, antepartum and postpartum period with regards to CVD risk. Additionally, it is hoped that these initiatives will also improve care of these women through improved collaboration between the cardiologist and the obstetrician.

References:

- World Bank Statistics -2018 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT?locations=FI-VE&year_high_desc=false Accessed July 28, 2019

- Centers for Disease Control Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Freproductivehealth%2Fmaternalinfanthealth%2Fpmss.html Accessed July 28, 2019.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologist (ACOG) Releases Comprehensive Guidance on How to Treat the Leading Cause of U.S. Maternal Deaths: Heart Disease in Pregnancy News Releases 2019. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/News-Releases/2019/ACOG-Releases-Comprehensive-Guidance-on-How-to-Treat-Heart-Disease-in-Pregnancy?IsMobileSet%3Dfalse&sa=D&ust=1564343293391000&usg=AFQjCNGL5pYJww-2z_FrcgJuZhx4vTeRGA Accessed July 28, 2019.

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Jordan LC, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, O’Flaherty M, Pandey A, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Turakhia MP, VanWagner LB, Wilkins JT, Wong SS, Virani SS; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee.Circulation. 2019 Mar 5;139(10):e56-e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) Committee Opinion No. 729: Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Awareness in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women.Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;131(1):e43-e48. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002459. Review.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) Committee Opinion No. 649: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology.Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;126(6):e130-4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001213

- Grandi SM, Filion KB, Yoon S, Ayele HT, Doyle CM, Hutcheon JA, Smith GN, Gore GC, Ray JG, Nerenberg K, Platt RW. Cardiovascular Disease-Related Morbidity and Mortality in Women With a History of Pregnancy Complications. Circulation. 2019 Feb 19;139(8):1069-1079.

- Grodzinsky A, Florio K, Spertus JA, Daming T, Schmidt L, Lee J,

Rader V, Nelson L, Gray R, White D, Swearingen K, Magalski

A.Maternal Mortality in the United States and the HOPE Registry.

Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2019 Jul 25;21(9):42. - . Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J, Sermer M, Kiess M, Rychel V,

Wald RM, Colman JM, Siu SC. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With

Heart Disease: The CARPREG II Study J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May

29;71(21):2419-2430