AHA Women in Cardiology Blog Series: DEVELOPING YOUR NICHE

Written by :Sherry-Ann Brown MD PhD and Renee P. Bullock-Palmer MD

As the subspecialty of cardiology continues to expand, opportunities abound for developing new niches. A few, among others, of great interest to Women In Cardiology, are Cardiovascular Disease in Women, Cardio-Obstetrics, and Cardio-Oncology (especially breast cancer), as well as Structural Heart Disease and Sports Cardiology, among others. How does one develop a new niche? Various strategies are summarized in this blog as outlined below. Review all of these tips and take away the ones most relevant to your career, needs, goals, and interests.

EX.C.E.L.

Gain as much exposure as you can to the area within your subspecialty to which you would like to devote most of your career (1). The more you learn, and the more experience you gain, the more you will become an expert.

Networking is incredibly important. This applies locally, Regionally, nationally, and globally. The more exposure you gain to your colleagues and other leaders at your institution and in your national societies (1), the more you will become known as an international expert.

As you introduce yourself and market your brand, you must be aware of your own capabilities, as well as the capabilities of your institution (1). Gauge your talents, strengths, passions, and personality. Assess your background, training, and preparation. Determine how to best apply your abilities. Evaluate the availability off the tools, resources, and personnel you will need to achieve your professional goal of building a niche.

Expectations are key. Early on, establish expectations that your institution may have of you as you develop a new program (1). Expectations for patient care, education, research, community engagement, and institutional citizenship should be made clear. Your own expectations of support for your vision, as well as administrative time as applicable, ought to be delineated.

Know your limitations (1), weaknesses, and opportunities for growth. Stretch and develop yourself, but not beyond where your intellect and training are willing to go. Know too the limitations of what you have available to you at your institution.

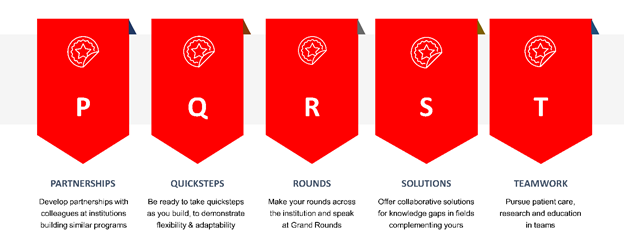

P.Q.R.S.T.

Cultivate partnerships (2) with colleagues at various stages of building similar programs at other institutions. Being able to share mutual insights on patients in your niche will be invaluable.

As you attempt different approaches in your program building, be willing to be flexible and take “quicksteps” (a lively combination of steps in ballroom dancing). Adaptability in medicine and leadership are key, just like in ballroom dancing.

Make your rounds among various departments and divisions. Offer to give and coordinate multidisciplinary grand rounds and short presentations at the division or department meetings. Provide didactics for the fellows, residents, and students.

Consider knowledge gaps or needs in complementary subspecialties locally, and devise solutions that can help other subspecialists and enhance collaboration (2).

Remember, patient care occurs best in the setting of teamwork (2). Build your team. Know your team. Lead your team.

3Ls

Look at the landscape to assess changes on the horizon within your area of expertise. Adapt to these changes. Cardiology as a field is always evolving in several areas and this will affect your practice. There are ever emerging fields, such as Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Cardio-Oncology, Interventional Echocardiography, and Cardio-Obstetrics. Therefore, it is important to never stop learning and acquiring new skills. Do not become stagnant, otherwise, there is a risk of becoming irrelevant. Lean in, be present both at your institution by participating actively at department meetings, volunteering for committees at your institution in your area of interest, and offering your expertise to lead and/or guide initiatives in your department.

3As

Find and align yourself with other experts locally, nationally, and even globally. This will help develop new leadership skills and promote your skills. Networking is crucial in one’s career and is one of the key benefits of professional societal involvement. Professional societal involvement is also a great way to learn and develop new research ideas.

Being accessible to your colleagues is important and will be helpful in developing your niche. Accessibility can be a great way to promote your practice, as well as increase your patient referral base.

Being accountable for your work is critical as you establish your niche. Accountability is a vital part of good patient care and being an effective leader in your practice.

2Ps

Find a platform to share your expertise either through outreach by giving educational talks to providers at local grand rounds, or dinner talks and participation in regional conferences and webinars. Participate in writing groups when the opportunity arises, and publish articles in your field. Opportunities for research may be either locally at your institution or nationally with multi-institutional national studies or registries.

Patient care is paramount, to demonstrate the effectiveness of your practice on clinical outcomes. After all, we entered this profession to take care of patients – do not practice in a vacuum. Excellent patient care will establish you as a meaningful contributor to the Cardiology service line at your institution.

Conclusion

Finding your niche is an important part of establishing your career. Never forget your career goals and focus and do not lose sight of these. We have outlined several strategies that may be customized to your practice environment and professional goals.

REFERENCES:

- Kilic A. How to develop a niche: Focus on adult cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(3):636-9.

- https://www.acc.org/membership/sections-and-councils/early-career-section/section-updates/2016/08/16/08/53/developing-a-niche-in-structural-heart-disease

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”