As someone who integrated her elementary school in Ohio (a Yeshiva), enrolled in an exclusive prep school in New England and became the first AA female in her cardiology program, I’ve spent my life analyzing how to adapt to environments in which I was different. When I enter an environment, I learn the lay of the land, identify key players, and observe interactions. I am a fourth-generation African American physician and was raised learning about my relatives’ experiences as minorities in medicine. If I, as early as age 9, could learn how to thrive in diverse environments others can too. I would like to share these experiences and make a case for diversity in cardiology. With this blog, I will help kick off the New Year with part 1 of a multiple part series that aims to define bias in medical training; openly make a case for and provide solutions towards inclusion in cardiology.

In this blog, I will review specific features that demonstrate bias, which can lead to less diversity in training programs. These are topics related to experiences in medicine that are shared by myself as well as my BIPOC and women colleagues.

Affirmative Action, The myth

There’s this assumption that BIPOC has a leg up unfairly given by Affirmative Action, and therefore are enrolled in academic programs without earning it and being unqualified. Truthfully, nepotism and ease of identifying mentors provide more opportunities than any small % quota which does not seem to translate to faculty positions. In research, at times I have had to become my own mentor to continue to propel myself forward. Without visible faculty mentors, it is difficult to envision a role in academic medicine which makes this career aspiration less likely for many BIPOC. The educational system’s balance as a whole has been skewed related to the American Caste system (consider reading Caste by Isabel Wilkerson). This affects testing metrics and exposure to certain educational experiences. However, with the right inclusion, training, and belief in someone; talented students will become great physicians and cardiologists. In fact, this idea that BIPOC is all unqualified is ironic; many of us feel we have to work twice as hard with a cool and steady temperament all the way through (think of President Obama) to get half as far. Despite strong backgrounds; I often hear colleagues make comments like: “ They are not as clinical.” I already know the race before hearing the full story. We can’t all be inept; not possible.

Double Standards/ Lack of Benefit of the Doubt

Double standards, a topic at this nation’s center as we watched different responses to the siege on Capitol Hill. In cardiology and medicine, it is not uncommon that the same errors in one person may receive a different response from leadership compared to another. One cardiologist stated that he, like many of his colleagues, inadvertently caused a coronary dissection. The response, however, was harsher than what his colleagues experienced for the same incident. One simple misunderstanding with a BIPOC resident or medical student led to unnecessary poor feedback to this resident that could have been remedied with a conversation. She was not given the benefit of the doubt like her peers would have; in fact, I don’t think the incident would have been reported at all considering how trivial it was. At times, we feel closely observed and overly scrutinized. At times by other women and BIPOC as well. Perhaps there is a “crabs in a barrel” mentality when there are so few represented in one place, this can actually create tension. What’s most difficult is, there’s less ability to be human; which is amplified when it seems as if there is not always a trustworthy authority to turn to. It may not be that one BIPOC placed in a leadership position; they may not want to rock the boat.

So we feel that we must work twice as hard; smile (wear the mask long before COVID19), with only marginal to no room for error (there is a great scene in the movie about the Tuskegee Airmen on HBO that highlights this point).

Abstract Feedback

Often we receive feedback that is very vague and abstract and seemingly more personal than constructive. It’s generally a vague comment that has one racking their brain over and over with no real tangible solution provided by the person giving the feedback; this was described in “Research: Vague Feedback Is Holding Women Back.” For example, I was once told, “You’re too confident.” How do I change my confidence? How can I be less confident, but at least somewhat self-assured? Do you see how this happens? Not too uncommonly we receive nonactionable feedback that has one racking their brain and can have an emotional impact. It’s distracting. Actionable feedback is more helpful especially if it is not something very personal and aimed more at patient care. One mentee of mine received an overall vague evaluation and marked her with critical deficiencies without good evidence. I did not want this practice to continue, and I wrote to the associate program director to describe the scenario and shared my concerns. It was determined that this evaluation was a mistake after a larger review. Imagine a situation had it stayed on her record; it could have had negative implications to her career, especially, when she is planning to pursue a selective fellowship.

Assumptions

During a medical school interview, I was asked if they should accept fewer women due to pregnancy. I was never comfortable sharing my pregnancy considering this was my first introduction. He assumed women couldn’t make these decisions, and that, affirmative action should be taken away (this was 2008; not long ago). I have also found that, before really knowing one’s interest, it is assumed a female cardiologist will pursue a career in imaging. I am often asked “ You’re doing imaging, right?” Or I’ve heard, “ she is an imager, typical.” This can impact cath scheduling if there are no fixed schedules for all fellows. In fact, scheduling is where bias can creep in ( I have heard of giving longer hours to BIPOC forcing one group of residents to threaten federal intervention.) This can be avoided with as much equal scheduling as possible (not always perfectly feasible) without assuming anything. Assumptions are not meant to be hurtful; it’s human nature. However, at times it may pigeonhole folks to roles that must end with women’s health, equity, or inclusion (exceptionally relevant roles). These folks can also have leadership roles related to other clinical interests as well.

Certainly, these may not all be unique to BIPOC and women; however, I hear similar stories over and over again, as if they are told by the same person. As we enter into a new era, I hope cardiology joins the future of progress. In parts II and III, I will answer why inclusion is important and some solutions on how to cultivate an inclusive specialty.

For this series, we will be discussing –

Part 1. My experience

Being hypnotized that I am lower in the caste system and limited. The emotion clouded my abilities and held me back from further progress. I have to prove my resume more than my colleagues every time and it’s exhausting. In research, I’ve felt like an outsider constantly having to build my own way and have been directly judged for lack of prolific publications.

Part 2. Why?

Embracing difference can help a program evolve (% diversity at Harvard ) it’s a win-win; a synergistic relationship in which we grow together. Representation matters, and to diversify the workforce will help the patients’ comfort and compliance.

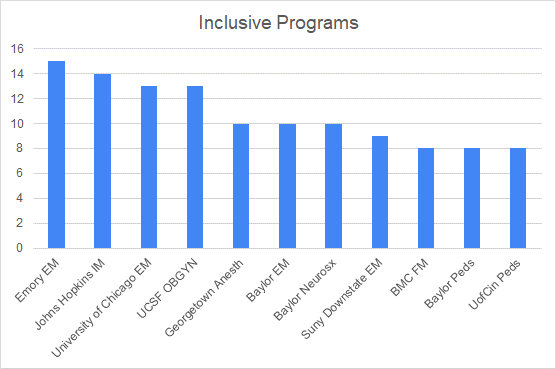

Part 3. How?

Aim for a standard similar to Goldman Sachs’s 25%1. Provide resources and assistance to BIPOC. Show up for each other. Engage ABC and uplift ; normalize discussing differences and being different. Check in with your BIPOC trainees’ wellbeings, if there are issues driven by bias speak up with your peers in a collegial way.

Reference

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2774738?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social_jamajno&utm_term=4395647160&utm_campaign=article_alert&linkId=108893385

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”