Vaping is a Public Health Problem. It’s Also an Equity Issue.

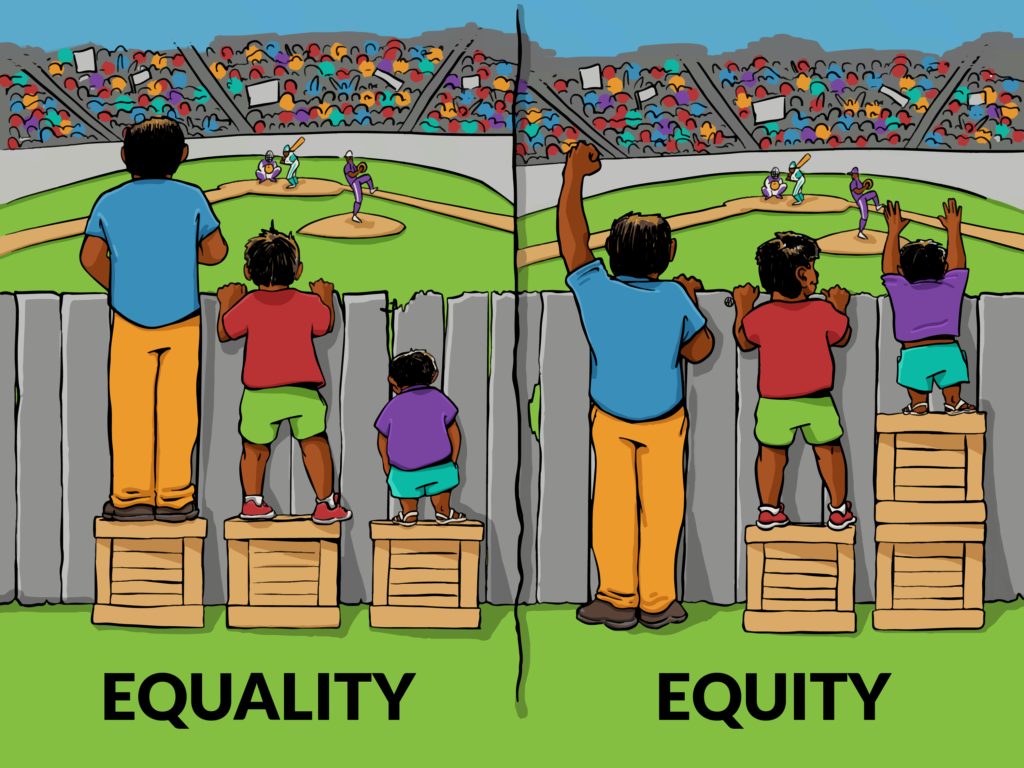

Image: Angus Maguire, via http://interactioninstitute.org/illustrating-equality-vs-equity/

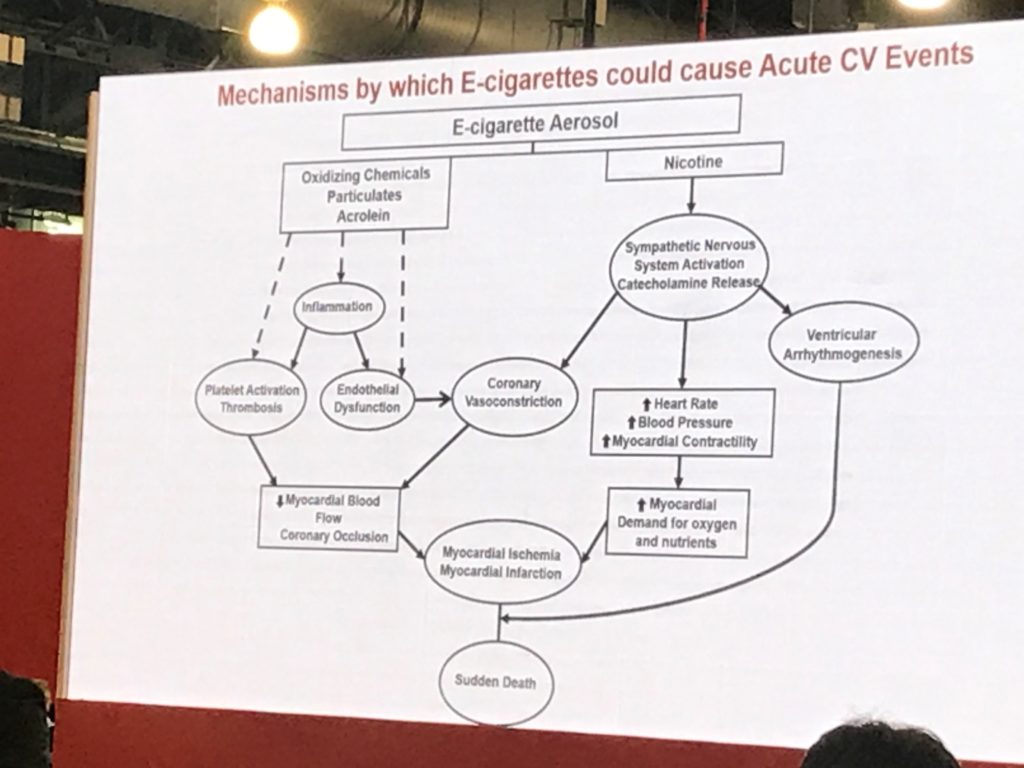

Vaping is a massive public health issue— and history shows us that public health issues often disproportionally affect vulnerable populations. While there has been some push-back from the vaping public about the scientific community’s alarm— focusing on the fact that the evidence of harm attributable to vaping isn’t yet fully developed— scientists and clinicians agree that the emerging pattern is deeply concerning, especially as it relates to children and adolescents. There are well-established theoretical and evidence-based reasons to associate vaping with cardiovascular disease and even death, but that’s beyond the scope of this discussion. What I will address is this: failing to address an imminent public health crisis early and aggressively can lead to real harm for vulnerable populations. Waiting for a preponderance of incontrovertible evidence before acting means that significant harm has already occurred. Intervening now is a chance to promote health equity.

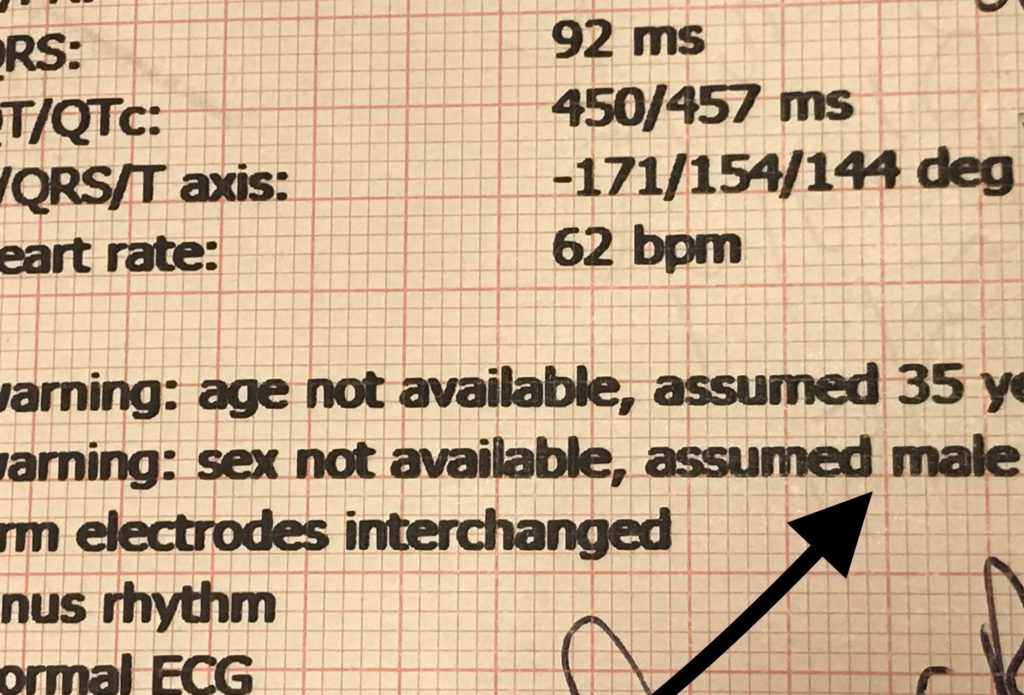

We know there are disparities in tobacco use among populations. There is higher prevalence in the LGBT community, those living in poverty, those with mental health disorders, those with substance use disorders, and those living in South and Midwest , an those living in rural areas (CDC, 2015). Some evidence suggests that disparities in the use and promotion of other tobacco products and e-cigarettes mirror trends in cigarette use and marketing. In a session at #AHA19 today, Dr. Michael Blaha (@MichaelJBlaha on Twitter) noted that vaping specifically is more common among men, LGBTQ people, unemployed people, and people with less than a college education. We also know that data may hide some populations, especially homeless, incarcerated, marginalized, non-English-speaking people. So yes, this an equity issue. As we in the health community face the specter of vaping-related health crises, we must look at the impact through an equity lens.

As recently announced, the AHA is pledging $20 million to fund research on youth vaping. This is part of a program including a public information campaign (#QuitLying and #EndTheLies) and policy initiatives. Priority research areas, per the AHA’s statement, include nicotine’s impact on adolescent brain development, the impact of nicotine and other compounds in e-cigarettes on the cardiovascular system, how devices, flavors and other chemicals influence addiction, how to treat nicotine addition in youth, whether e-cigarettes are effective for smoking cessation, and what the impact of regulation is. As we scientists and clinicians proceed, we must design our research to address:

- Racial, ethnic, gender, & socioeconomic factors

- Comorbidities, including mental health disorders, substance use disorders, and disability

- Whether proposed policy and information/communication solutions are effectively reaching those with the highest need

Some healthcare practitioners and researchers didn’t get the tools during their education to design equitable research and programs. If this is you, check out the resources below. Then, get your voice out— participate in research design and policy initiatives, communicate to the public and your professional community, and remember to put health equity at the top of the agenda.

Resources & References:

-Centers for Disease Control (2015). Best Practices for Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best-practices-health-equity/pdfs/bp-health-equity.pdf (much of this information is applicable to vaping, as well as other public health concerns).

-MPH@GW: Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University. What’s the diffrence between equity and equality? Available at: https://publichealthonline.gwu.edu/blog/equity-vs-equality/

-Research presented at #AHA19 about vaping: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/e-cigarettes-take-serious-toll-on-heart-health-not-safer-than-traditional-cigarettes

The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.

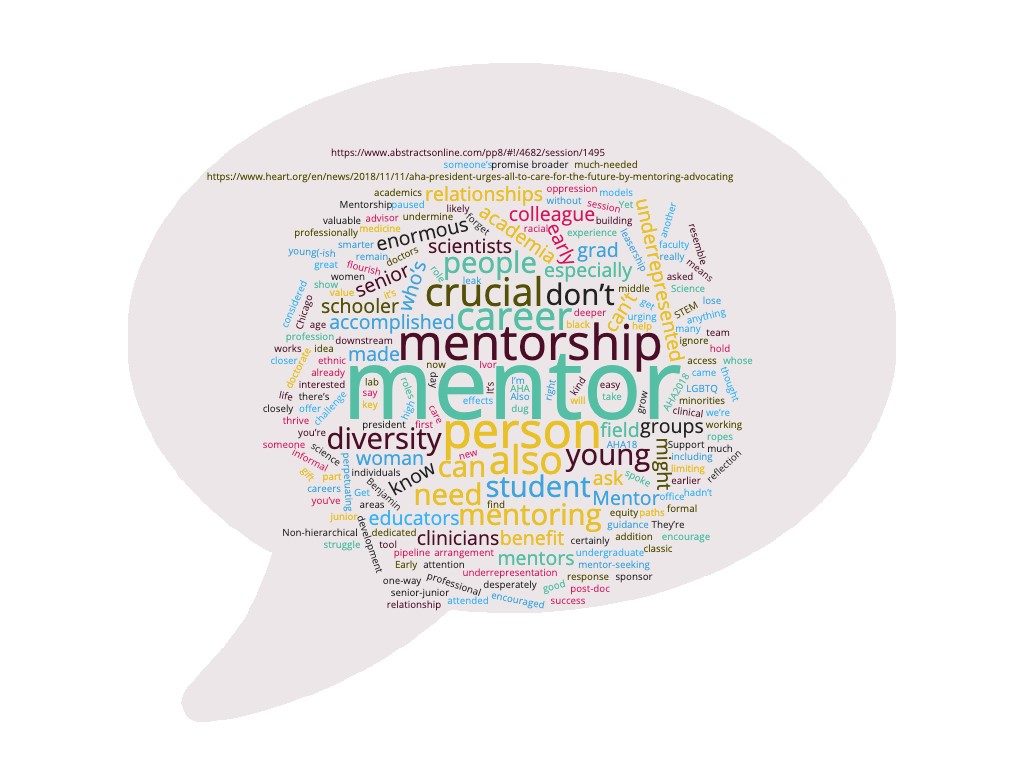

Early in our careers, academics are encouraged to find good mentors. You need an advisor to get a doctorate, and this person is a mentor. You might be working in someone’s lab as a grad student or post-doc, and that person can be a mentor. You might be junior faculty and have a senior mentor to show you the ropes. There are formal mentorship relationships and informal mentoring relationships, and you’ve likely had both in your career. They’re a key part of professional development.

Early in our careers, academics are encouraged to find good mentors. You need an advisor to get a doctorate, and this person is a mentor. You might be working in someone’s lab as a grad student or post-doc, and that person can be a mentor. You might be junior faculty and have a senior mentor to show you the ropes. There are formal mentorship relationships and informal mentoring relationships, and you’ve likely had both in your career. They’re a key part of professional development.

I’m a researcher, but I’m also a nurse. Nurses are used to talking to people about complex health topics in plain language. We are often the ones helping patients wade through jargon, numbers, and data they don’t have the experience to interpret otherwise. Many nurses can do this brilliantly on the individual level – nurse to patient. As scientists, though, we have a responsibility to translate specialized knowledge on a larger scale, and most of us are ill prepared to take on this task. In graduate school, we are taught how to present our findings to other scientists, but many of us are at a loss as to how to talk to people without a science background about our work.

I’m a researcher, but I’m also a nurse. Nurses are used to talking to people about complex health topics in plain language. We are often the ones helping patients wade through jargon, numbers, and data they don’t have the experience to interpret otherwise. Many nurses can do this brilliantly on the individual level – nurse to patient. As scientists, though, we have a responsibility to translate specialized knowledge on a larger scale, and most of us are ill prepared to take on this task. In graduate school, we are taught how to present our findings to other scientists, but many of us are at a loss as to how to talk to people without a science background about our work. Still, the general public doesn’t read the New England Journal, so how do we bridge the gap between the academic press and the popular press? How can we as scientists and health care professionals communicate effectively to the public? We don’t have to go it alone – science journalists are professional communicators. It’s their job to craft science-based stories that are both accurate and compelling.

Still, the general public doesn’t read the New England Journal, so how do we bridge the gap between the academic press and the popular press? How can we as scientists and health care professionals communicate effectively to the public? We don’t have to go it alone – science journalists are professional communicators. It’s their job to craft science-based stories that are both accurate and compelling.