Data Science and Coding for Clinicians – Where to Start

Medicine is seeing an explosion of data science tools in clinical practice and in the research space. Many academic centers have created institutions tailored to integrating machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) into medicine, and major associations including the AHA have created funding opportunities and software tools for clinicians interested in harnessing the promise of big data for their research.

While knowledge on the underlying algorithms and writing code is not necessary to lead a multidisciplinary team working in this space, there are those that want a working knowledge of what is happening under the hood. Thankfully, the computer science (CS) and AI communities have numerous free, online resources to help with this. As I embark on a Masters in Artificial Intelligence, I have used these courses as prep work and found them to be highly educational.

- Python for Everybody – By Dr. Charles R. Severance, University of Michigan

This course is meant to get those with no programming background up and running with Python. It focuses on understanding the underlying syntax of the language and the various data structures that come standard in Python. It also touches on web applications, SQL, and data visualization. Thorough, but approachable, this is a great place to start.

- CS50x – By Dr. David Malan, Harvard University

One of the most popular courses at Harvard, this course is an intensive introduction to computer science, focusing on key concepts and using various programming languages to illustrate them. The first half or so of the course teaches you to program in C, a low-level language that illustrates how a computer really functions, before moving on to Python (and various Python frameworks), SQL, and web programming. While the juice is definitely worth the squeeze, this course is a commitment and takes significant mental energy to get through.

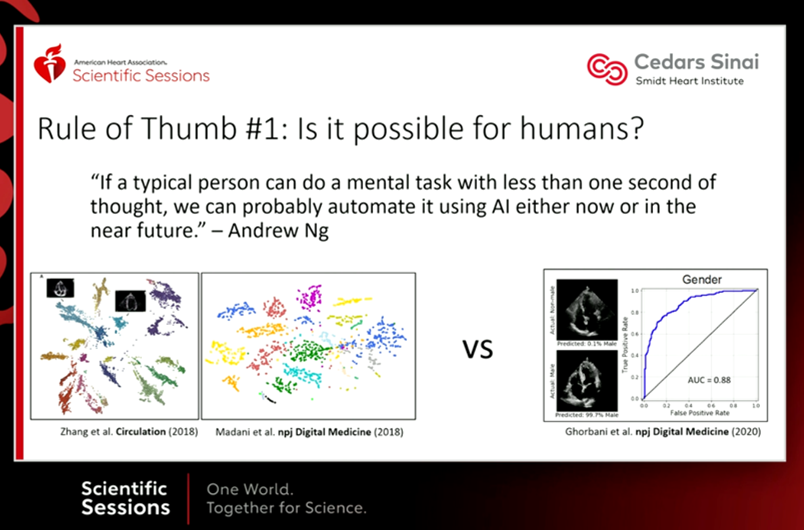

- Machine Learning – By Dr. Andrew Ng, Stanford

One of the courses that popularized the massive open online course (MOOC) revolution, here AI visionary Dr. Ng takes you through a survey of ML/AI algorithms with real world examples and problem sets to work through. The main programming language is MATLAB. This course is enough to give you a basic overview of how these algorithms run and the types of data they are best at handling, serving as a solid introduction to the field.

- Machine Learning for Healthcare – By Peter Szolovits and David Sontag, MIT

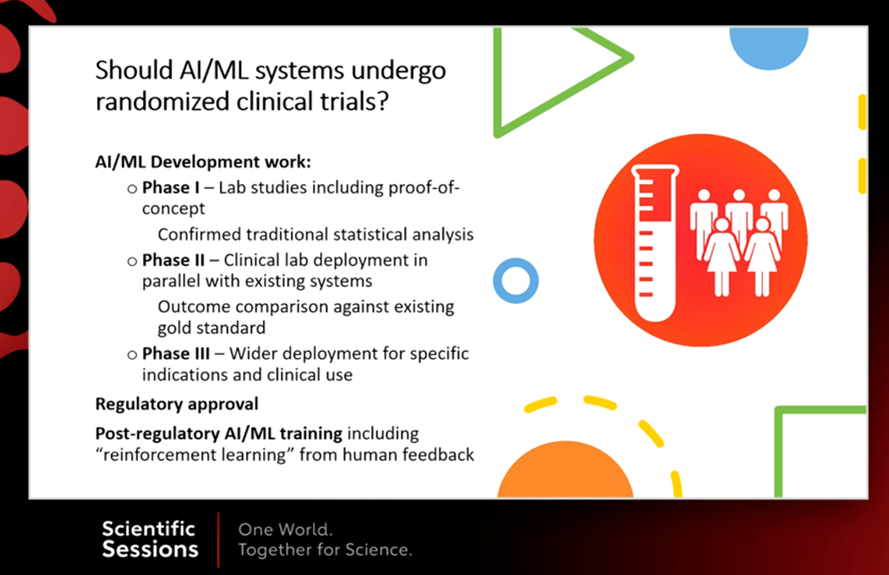

Healthcare in general and the data it generates is unique, posing challenges distinct from other fields where ML/AI are commonly employed. This course highlights these points through a thorough investigation of healthcare data, common questions clinicians ask in routine patient care, and the clinical integration of ML. It touches on many different topics, including ML for cardiac imaging, natural language processing and clinical notes, and reinforcement learning. No coding is required for this course.

While these courses are just a start, they provide the groundwork for further investigation. in many cases, they are enough to develop an intuition of more complex material including deep learning. If these are topics that interest you, I encourage you to jump on in!

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”

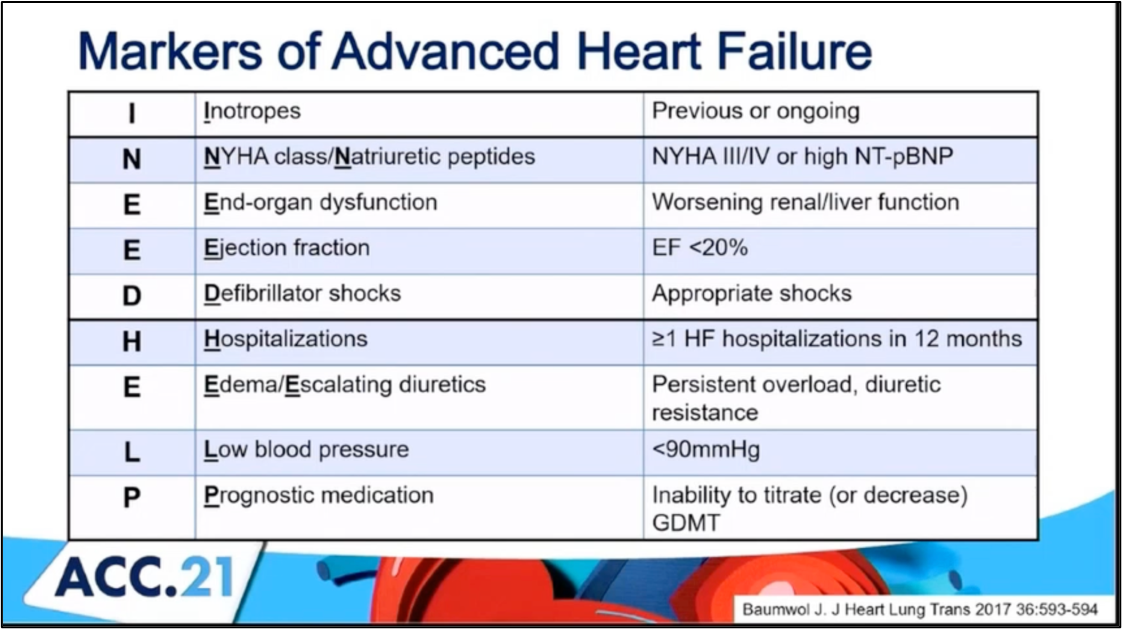

#ACC21 came and went, bringing the usual flurry of practice-changing clinical trials, new scientific theories and inquiries, and a wealth of creative ideas showcased through poster presentations. While the virtual format is quite the departure from the in-person atmosphere, it allows flexibility in viewing sessions on-demand and allows individuals that may have an otherwise challenging time traveling to join the discussion. Aside from the trials and presentations that got the most headlines, I wanted to highlight a talk within the advanced heart failure space that expanded on a challenging clinical scenario we encounter routinely. This blog contains screenshots that are directly from the talk Moving Beyond NYHA Class: Risk Stratification and Prognosis in Advanced Heart Failure (within Session 603 The Advanced Heart Failure Therapies of LVAD and Transplant: Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How?) by Dr. Garrick Stewart from Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

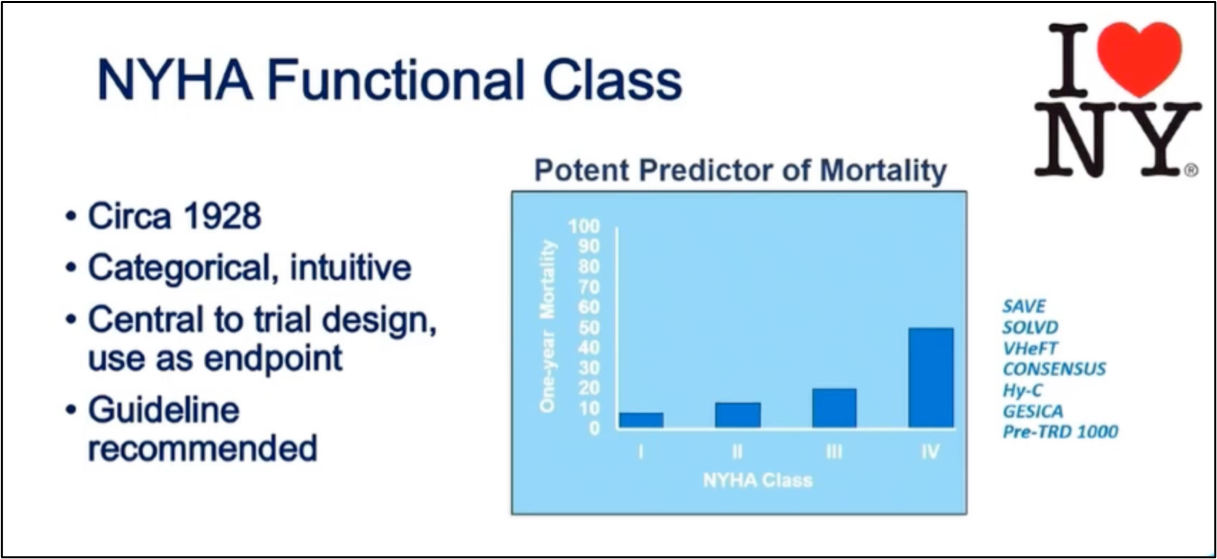

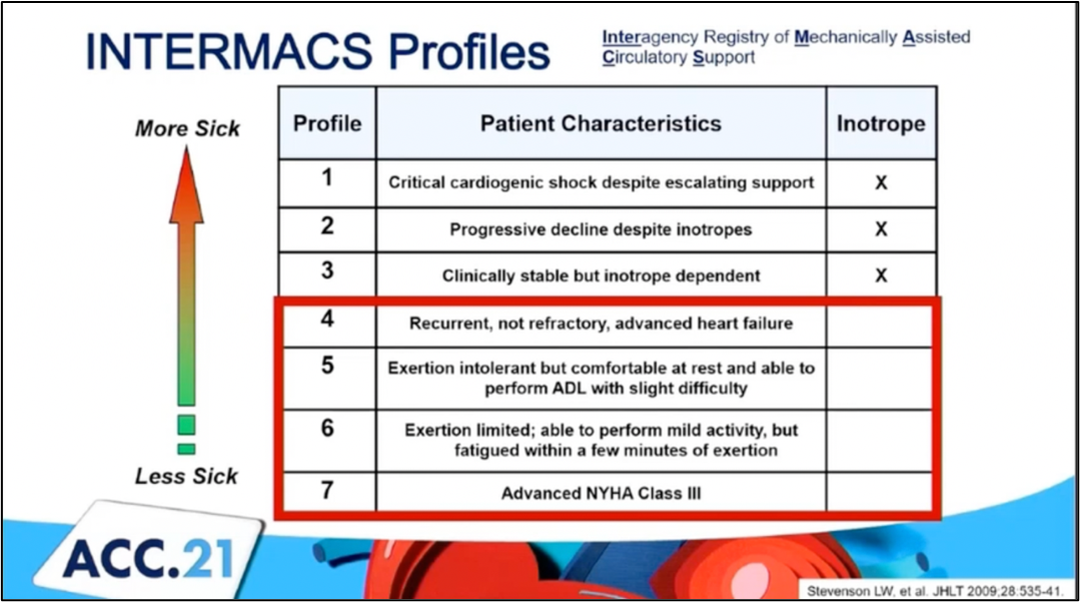

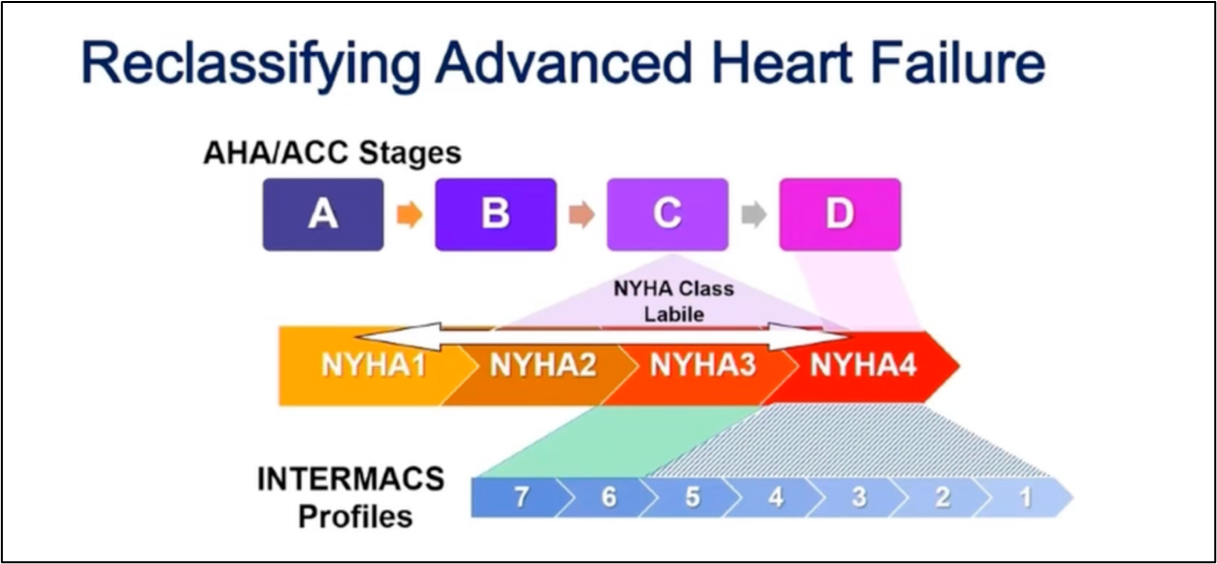

#ACC21 came and went, bringing the usual flurry of practice-changing clinical trials, new scientific theories and inquiries, and a wealth of creative ideas showcased through poster presentations. While the virtual format is quite the departure from the in-person atmosphere, it allows flexibility in viewing sessions on-demand and allows individuals that may have an otherwise challenging time traveling to join the discussion. Aside from the trials and presentations that got the most headlines, I wanted to highlight a talk within the advanced heart failure space that expanded on a challenging clinical scenario we encounter routinely. This blog contains screenshots that are directly from the talk Moving Beyond NYHA Class: Risk Stratification and Prognosis in Advanced Heart Failure (within Session 603 The Advanced Heart Failure Therapies of LVAD and Transplant: Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How?) by Dr. Garrick Stewart from Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Stewart starts with an overview of how we think about and classifies patients who have heart failure, starting with the history of the New York Heart Association Class grading schema. While it is simple to use and universally known, its limited in its ability to discriminate how sick those with heart failure truly are. Specifically, it cannot tell you who is at the highest risk for morbidity and mortality. To try and address those specifically with advanced heart failure, the INTERMACS Profiles were created. He outlines in his talk how these schemes are related

Dr. Stewart starts with an overview of how we think about and classifies patients who have heart failure, starting with the history of the New York Heart Association Class grading schema. While it is simple to use and universally known, its limited in its ability to discriminate how sick those with heart failure truly are. Specifically, it cannot tell you who is at the highest risk for morbidity and mortality. To try and address those specifically with advanced heart failure, the INTERMACS Profiles were created. He outlines in his talk how these schemes are related

Reference:

Reference: