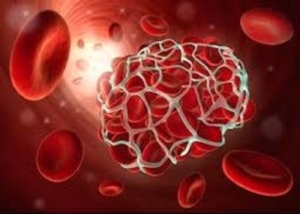

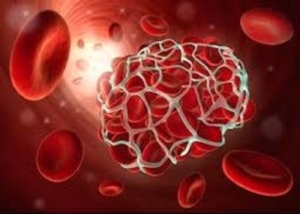

Initially known as a predominantly respiratory disease, there is currently no doubt that COVID-19 is increasingly emerging as a prothrombotic condition. Observational studies, as well as published and anecdotal case reports have highlighted the thrombotic manifestations of COVID-19, with particular emphasis on the strong association between D-dimer levels and poor prognosis.1,2 While the COVID-19 clotting narrative has been dominated by venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism (PE),3-5 macro-thrombosis of the coronary6 and cerebral circulations7 have also been reported, as have the prevalence of microthrombi arising from endotheliitis in other sites.8

The pathophysiology

Some authors have described this SARS-CoV-2 induced hypercoagulability as ‘thromboinflammation’, an interplay between inflammation and coagulability leading to sepsis-induced-coagulopathy (SIC) and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy in severe COVID-19 cases.9 The pathophysiology is still incompletely understood but may be largely explained by the three components of Virchow’s triad:

Endothelial dysfunction: SARS-CoV-2 virus enters the host using the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is widely expressed not only in the alveolar epithelium of the lungs but also vascular endothelial cells, which traverse multiple organs.8 Varga, et al. reported this concept of COVID-19 ‘endotheliitis’ in their paper, explaining how endothelial dysfunction, which is a principal determinant of microvascular dysfunction, shifts the vascular equilibrium towards vasoconstriction, organ ischaemia, inflammation, tissue oedema, and a procoagulant state, leading to clinical sequalae in different vascular beds.8 Complement-mediated endothelial injury leading to hypercoagulability has also been suggested.10

Hypercoagulability: SARS-CoV-2-induced hypercoagulability has also been attributed as a consequence of the ‘cytokine storm’ that precipitates the onset of a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, resulting in the activation of the coagulation cascade.11,12 However, whether the coagulation cascade is directly activated by the virus or whether this is the result of local or systemic inflammation is not completely understood.12

Stasis: Critically ill hospitalized patients, irrespective of pathophysiology are prone to vascular stasis as a result of immobilization.13

Currently available data: predominantly observational studies

In some of the earliest data emerging from Wuhan, Tang, et al. reported significantly higher markers of coagulation, especially prothrombin time, D-dimers and FDP levels, among non-survivors compared to survivors of SARS-COV2 novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP), suggesting a common coagulation activation in these patients.1

Subsequently, Zhou, et al., reported that D-dimer levels, along with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and IL-6 were clearly elevated in non-survivors compared with .14 This was highlighted in one of the earliest CCC-ACC webinars on COVID-19 in March 2020, by Professor Cao, who drew emphasis on their data where D-Dimer >1μg/mL was an independent risk factor for in-hospital death, with an odds ratio of 18.42 (p=0.0033). 14,15

In another single centre study among 81 severe NCP patients from Wuhan, Ciu, et al., observed that D-dimer levels >1.5 μg/mL had a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 88.5% for detecting VTE events.3 In an observational study of 343 eligible patients by Zhang, et al., the optimum cutoff value of D-dimer level on admission to predict in-hospital mortality was 2.0 µg/ml with a sensitivity of 92.3% and a specificity of 83.3%.16

With a shift in the epicenter of the pandemic, data from Europe highlighted the prevalence of both arterial and venous thrombotic manifestations among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, many of whom received at least standard doses of thromboprophylaxis.5,13

Most recent data from an observational cohort of 2,773 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in New York, showed that in-hospital mortality was 22.5% with anticoagulation and 22.8% without anticoagulation (median survival, 14 days vs 21 days).17 Confounded by the immortal time bias, among others, these data underscore the pressing need for well-designed RCT’s to answer this burgeoning therapeutic dilemma.

Antithrombotic therapy: What is the guidance?

As physicians learn more about this clotting conundrum, there is an increasing need for evidence-based guidance in treatment protocols, especially pertaining to anticoagulation dosing and the role of D-dimers in deciding on optimum therapeutics.

International consensus-based recommendations published by Bikdeli, et al. in the Journal of American College of Cardiology on 15th April 2020 recommend risk stratification for hospitalized COVID-19 patients for VTE prophylaxis, with high index of suspicion.11 They further state that, as elevated D-dimer levels are a common finding in patients with COVID-19, it does not currently warrant routine investigation for acute VTE in absence of clinical manifestations or supporting information. For outpatients with mild COVID-19, increased mobility is encouraged with recommendations against the indiscriminate use of VTE prophylaxis, unless stratified as elevated-risk VTE.

The majority of panel members considered prophylactic anticoagulation to be reasonable for hospitalized patients of moderate to severe COVID-19 without DIC, acknowledging that there is insufficient data to consider therapeutic or intermediate dose anticoagulation; the optimal dosing however, remains unknown.11 Furthermore, extended prophylaxis, with low-molecular weight heparin or direct oral anticoagulants for up to 45 days after hospital discharge, was considered reasonable for patients with low-bleeding-risk patients and elevated VTE (i.e. reduced mobility, comorbidities and, according to some members, elevated D-dimer more than twice the upper normal ).11

A Dutch consensus published shortly after on the 23rd April 2020, also recommends prophylactic anticoagulation for all hospitalized patients, irrespective of risk scores.12 Imaging for VTE and therapeutic anticoagulation recommendations are largely guided by admission D-dimer levels and their progressive increase, based on serial testing during hospital stay, in addition to clinical suspicion. A lower threshold for imaging has been recommended if D-dimer levels increase progressively (>2,000-4,000 μg/L), particularly in presence of clinically-relevant hypercoagulability. However, in contrast to the consensus document published in JACC, the Dutch guidance recommends that, where imaging is not feasible, therapeutic-dose LMWH without imaging may be considered if D-dimer levels increase progressively (>2,000-4,000 μg/L), in settings suggestive of clinically relevant hypercoagulability and acceptable bleeding risk.12

The need for RCT’s

Even as we scramble to clarify the pathophysiology, the urgency to establish evidence-based standard of care in terms of anticoagulation has never been greater. Dosing is a matter of hot debate (prophylactic versus intermediate versus therapeutic), especially considering the risk of bleeding that can arise from indiscriminate anticoagulation.

Furthermore, while we have data that underscores increased coagulation activity (D-dimers in particular) as a potential risk marker of poor prognosis, D-dimers remain non-specific and there is insufficient evidence as to whether they can be used to guide decision-making on optimum anticoagulation doses among patients with COVID-19.

The existing evidence on thrombotic complications and their treatment has been primarily derived from non-randomized, relatively small and retrospective analyses. Such observational studies have been hypothesis generating at best, and in the absence of robust evidence, randomized clinical trials are imperative to address this critical gap in knowledge in an area of clinical equipoise. And there are quite a few to watch out for, as evidenced by a quick search in Clinicaltrials.gov, some of which are already recruiting.

RCT’s of therapeutic vs prophylactic anticoagulation:

Currently recruiting at University Hospital, Geneva, this trial randomizes 200 hospitalized adults with severe COVID-19 to therapeutic anticoagulation versus thromboprophylaxis during hospital stay. The primary endpoint is a composite outcome of arterial or venous thrombosis, DIC and all-cause mortality at 30 days.

This open label RCT of hospitalized COVID-19 positive patients with a D-dimer >500 ng/ml is currently recruiting at NYU Langone Health (estimated enrolment of 1000 patients). Patients will be randomized to higher-dose versus lower-dose (e.g. prophylactic-dose) anticoagulation in 1:1 ratio. Primary endpoints include incidences of cardiac arrest, DVT, PE, MI, arterial thromboembolism or hemodynamic shock at 21 days and all-cause mortality at 1 year.

This randomized, open-label trial sponsored by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) commencing recruitment mid-May, will randomize 300 participants with elevated D-dimer > 1500 ng/ml to therapeutic versus standard of care anticoagulation in a 1:1 ratio, based on MGH COVID-19 Treatment Guidance. Designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation, primary outcome measures include the composite efficacy endpoint of death, cardiac arrest, symptomatic DVT, PE, arterial thromboembolism, MI, or hemodynamic shock at 12 weeks, as well as a major bleeding event at 12 weeks.

- Enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients: Comparison of 40 mg o.d. Versus 40 mg b.i.d. A Randomized Clinical Trial (X-COVID 19)[https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04366960]

This open-label multi-centre RCT will recruit 2712 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Milan, Italy, randomized to subcutaneous enoxaparin 40 mg daily versus twice daily within 12 hours after hospitalization, to assess the primary outcome measure of venous thromboembolism detected by imaging at 30 days.

RCT of intermediate vs prophylactic dose anticoagulation:

A cluster-randomized trial of 100 participants, IMPROVE-COVID, sponsored by Columbia University will compare the efficacy of intermediate versus prophylactic doses of anticoagulation in critically ill patients with COVID-19. The primary outcome measure is the composite of being alive and without clinically-relevant venous or arterial thrombotic events at discharge from ICU or at 30 days (if ICU duration ≥30 days).

Even months later, COVID-19 continues to baffle clinicians. But what has been crystal clear right from the outset is that there is no alternative to evidence-based practice, and it stands true in the face of this clotting conundrum as well.

Image from Shutterstock

References

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844-847.

- Zhang L, Yan X, Fan Q, Liu H, Liu X, Liu Z, et al. D-dimer levels on admission to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with Covid-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr 19. doi: 10.1111/jth.14859.

- Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F: Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia.. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr 9. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830

- Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, Parmentier E, Duburcq T, Lassalle F, et al. Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Circulation. 2020 Apr 24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430.

- Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, et al., on behalf of the Humanitas COVID-19 Task Force. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020; 191: 9–14.

- Dominguez-Erquicia P, Dobarro D, Raposeiras-Roubín S, Bastos-Fernandez G, Iñiguez-Romo A. Multivessel coronary thrombosis in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia, European Heart Journal, , ehaa393, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa393

- Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, et al. Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 28.

- Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 May 2;395(10234):1417-1418

- Connors JM, Levy JH. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr 17. doi: 10.1111/jth.14849.

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, Nuovo G, Salvatore S, Harp J, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 15]. Transl Res. 2020;S1931-5244(20)30070-0. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, et al. COVID-19 and Thrombotic or Thromboembolic Disease: Implications for Prevention, Antithrombotic Therapy, and Follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 15:S0735-1097(20)35008-7

- Oudkerk M, Büller HR, Kuijpers D, van Es N, Oudkerk SF, McLoud TC, et al. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Thromboembolic Complications in COVID-19: Report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020 Apr 23:201629.

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020 Apr 10. pii: S0049-3848(20)30120-1. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013.

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al.Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1054-1062.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjEhV68GcD8&feature=youtu.be

- Zhang L, Yan X, Fan Q, Liu H, Liu X, Liu Z, Zhang Z. D-dimer levels on admission to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with Covid-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr 19. doi: 10.1111/jth.14859. [Epub ahead of print]

- Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, Russak A, Glicksberg BS, Levin MA, et al. Association of Treatment Dose Anticoagulation with In-Hospital Survival Among Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 6]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”