Since some of the risk factors for atherosclerosis such as eating fast food, lacking physical activity, and developing diabetes appeared with the modernization of our societies, it is natural to think that atherosclerosis is a disease of the modern world.

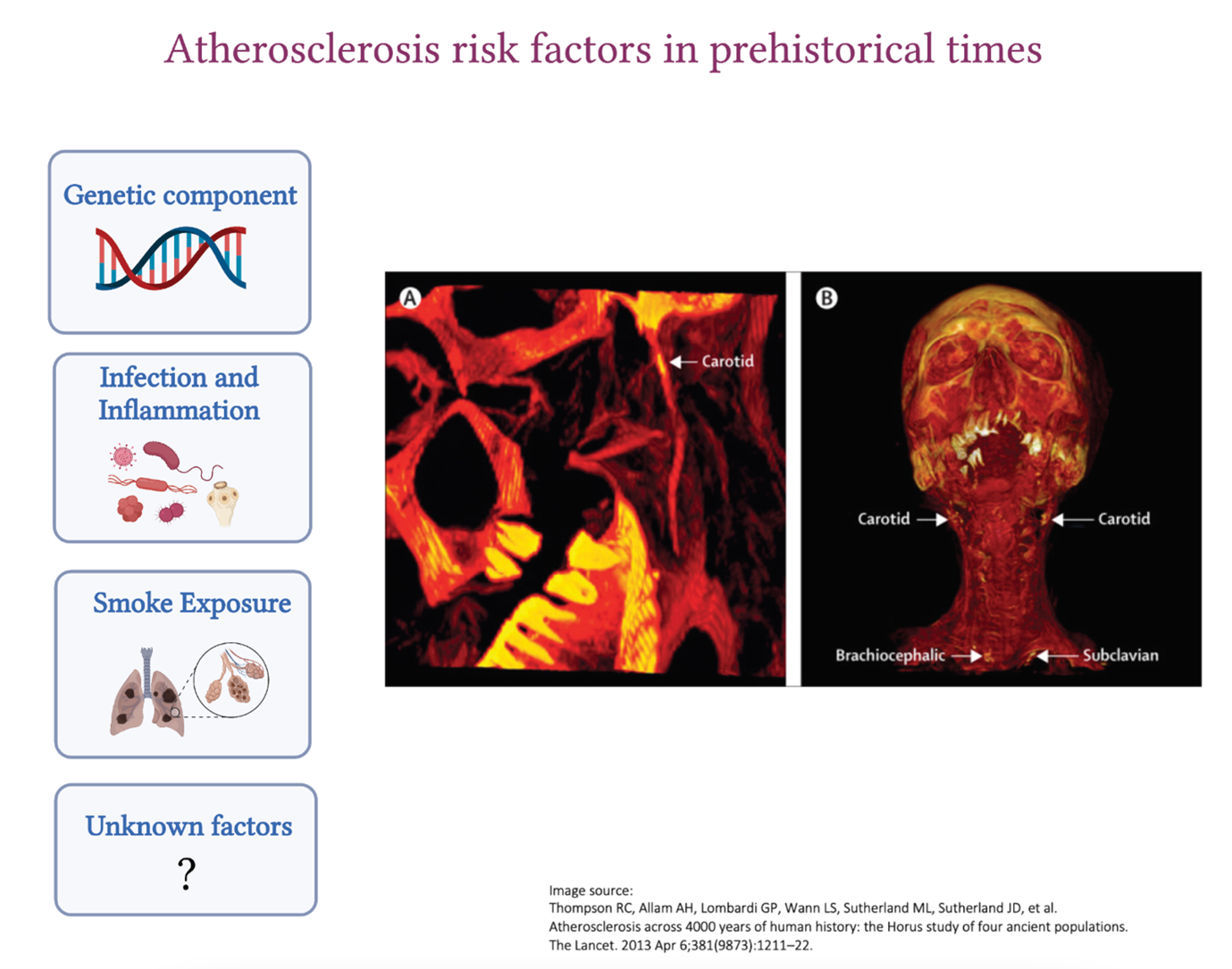

However, atherosclerosis also existed in the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Peru, the American Southwest, and the Aleutian Islands who were all pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers. These observations were pioneered by Czermak in 1852 and taken further by the Horus study published by The Lancet in 2013 where vessel calcification was detected in 34% of the 137 mummies examined. The location of atherosclerosis was very similar to what we see nowadays. The aorta, as well as the femoral, tibial and carotid arteries, were affected, and in older mummies, atherosclerosis was detected in more than one vascular bed. The mummies who were 43 years old at the age of death were more likely to have atherosclerosis compared to those who were 32, highlighting the importance of advanced age in the development of the disease, which we also see nowadays. William Murphy and his colleagues also found carotid calcific atherosclerosis in the Otzi iceman from 3300 BCE.

Since ancient people had a very different lifestyle compared to modern humans, what were the reasons that lead to the development of atherosclerosis back then?

Genetic contribution

Humans have an innate predisposition to atherosclerosis. We now know how important this genetic link is to the disease as the discovery of novel genes involved in atherosclerosis is allowing the development of novel therapies (PCSK9 for example).

Gain of function mutations in lipid-related genes (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9 etc.) cause increased life-long exposure to LDL-C which could not be treated in ancient times. Not to mention the additive contribution of polymorphisms in different genes to atherosclerosis development which we have only started to understand recently (polygenic risk scores).

Inflammation

We now know the major contribution of inflammation to atherosclerosis and how chronic inflammation, which we see in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, increases the risk of developing atherosclerosis.

Ancient people had a high exposure to infections, such as tuberculosis and syphilis, against which they had no antimicrobial or vaccines. Chronic inflammation as a result of recurrent untreated infections may have contributed to atherosclerosis development.

Close proximity of these ancient populations to contaminated waters rich in microbes and parasites (such as Schistosoma species, Trichinella spiralis, Taenia species (tapeworm), Plasmodium falciparum (malaria) could have also increased the risk. Systemic inflammation caused by chronic infections in ancient populations could very well have accelerated the development of other inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis. Throughout the years, constant exposure to infections could have led to the selection of genes that provide a strong and effective inflammatory response to Homo sapiens which is only showing to be deleterious nowadays as heightened inflammatory reactions accelerate atherosclerosis and other diseases associated with aging.

Smoke inhalation

Indoor smoke is a risk factor for coronary heart disease and cancer. Ancient people used firewood for the majority of their activities (heating, cooking, and lighting) and their home structures, which were mostly subterranean, had little access to ventilation. Soot deposits were identified in the inner surface of the ribs from burials in southern Turkey suggestive of anthracosis. It was also shown that tobacco was also commonly used in ancient civilizations (especially the Peruvians) which, we now know, contributes to increased inflammation and accelerate atherosclerosis development.

Ancient vs modern atherosclerotic plaque

It remains unclear how the features of the atherosclerotic plaque evolved over the years. Calcifications, which are the ends-stage of atherosclerosis, is what is observed in the remains of the ancient plaques seen in some mummies who were probably important people in their communities. However, we have no clue about the composition of these plaques back then since most of the cellular components would have degraded.

Ancient people who developed atherosclerosis might have not lived long enough to die as a result of their plaque rupturing because their life ended in a tragic fight, a deadly infection or they were poisoned by their enemies. This makes it harder for us to understand if the exposure of ancient people to atherosclerotic risk factors was important enough for them to die from this disease or whether this disease evolved to become more deadly during our modern times. Did the features of what we now call ‘vulnerable plaque’ (high lipid content, thin fibrous cap and presence of intraplaque hemorrhage) exist back then or did the plaque display more stable features?

It may be that since infections, wars and famines are less common in our modern world, people now live long enough to die from the consequences of atherosclerosis which has certainly evolved with our modern lifestyles. However, regardless of the era, atherosclerosis has always been lurking in the shadows throughout the evolution of Homo sapiens, displaying a different face as the years pass by.

References

- Thompson RC, Allam AH, Lombardi GP, Wann LS, Sutherland ML, Sutherland JD, et al. Atherosclerosis across 4000 years of human history: the Horus study of four ancient populations. The Lancet. 2013 Apr 6;381(9873):1211–22.

- Walker EG. Evidence for prehistoric cardiovascular disease of syphilitic origin on the Northern Plains. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1983;60(4):499–503.

- Thomas GS, Wann LS, Allam AH, Thompson RC, Michalik DE, Sutherland ML, et al. Why Did Ancient People Have Atherosclerosis?: From Autopsies to Computed Tomography to Potential Causes. Glob Heart. 2014 Jun 1;9(2):229–37.

- Murphy WA, Nedden D zur, Gostner P, Knapp R, Recheis W, Seidler H. The Iceman: Discovery and Imaging. Radiology. 2003 Mar;226(3):614–29.

- Clarke EM, Thompson RC, Allam AH, Wann LS, Lombardi GP, Sutherland ML, et al. Is atherosclerosis fundamental to human aging? Lessons from ancient mummies. J Cardiol. 2014 May 1;63(5):329–34.

- Marchant J. Mummies reveal that clogged arteries plagued the ancient world. Nature [Internet]. 2013 Mar 11 [cited 2022 Mar 20]; Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2013.12568

“The views, opinions, and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness, and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions, or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke, or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”