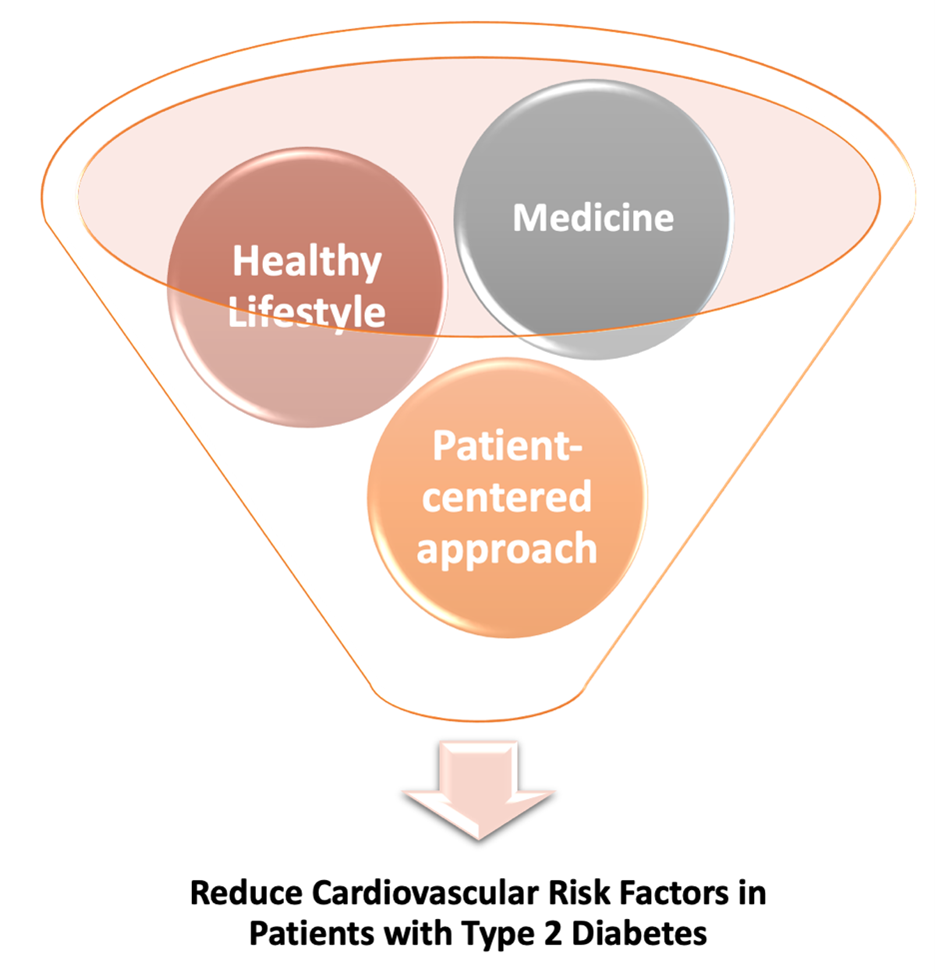

The prevalence of diabetes is increasing at an alarming rate, with more than 34 million Americans suffering from diabetes1. Patients with type 2 diabetes make up 90% to 95% of total diabetes cases1. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the principal cause of death and disability in type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients2. American Heart Association (AHA) recommends a comprehensive and patient-centered approach involving lifestyle management and pharmacological interventions to manage cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, glycemia, blood pressure (BP), and lipid abnormalities, in type 2 diabetes patients3.

A healthy lifestyle can substantially lower the risk of CVD events in type 2 diabetic patients. Lifestyle management involves physical activity, nutrition, psychological and emotional well-being, and smoking cessation3. The lifestyle interventions using meal replacement products and at least 175 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity /week, with a calorie goal of 1200 to 1800 kcal per day (with <30% from fat and >15% from protein), resulted in weight loss and hemoglobin A1c. Individuals with either ≥10% reduction in their body weight or >2 metabolic equivalent increase in fitness experienced reductions in cardiovascular outcomes; however, the rate of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was not reduced4. Mediterranean, vegetarian, low-carbohydrate, and diets rich in protein and nuts can lower blood glucose and body weight in type 2 diabetes patients3. Mediterranean diet over 4.8 years exhibited the highest benefits in blood glucose regulation and 29% of CVD events3,5. Further, increased exercise and physical activity can improve blood glucose, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, and inflammation in type 2 diabetes3. American Diabetes Association (ADA) has recommended more than recommends ≥150 minutes/week of moderate-to-vigorous intensity aerobic activity with no more than 2 days of inactivity in diabetes patients3,6. Including 2-3 sessions/week each of resistance and balance training is also recommended. Further, vigorous activity for a short duration (>75 minutes/week) or interval training is beneficial3,7. Patients with BMI ≥27 kg/m2 can use US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved weight loss medication. Orlistat, lorcaserin, liraglutide, naltrexone/bupropion are some of the weight management drugs approved by FDA have demonstrated ability to lower A1c3. Liraglutide at a lower dose can reduce cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients8. However, medicines should be immediately stopped if weight loss after 3 months is less than 5% or any safety concerns arise. Patients with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 or BMI 35.0 to 39.9 kg/m2 with no benefit with nonsurgical methods can consider metabolic surgery3. The long-term effects of weight-loss drugs and metabolic surgery on reducing cardiovascular events are yet to be studied.

Smoking is linked with abnormal lipid profile, worsening of glycemic measures, and increased pro-inflammatory marker in type 2 diabetes. Therefore, cessation of smoking is recommended3. Interestingly, light to moderate alcohol consumption compared to no drinking, particularly wine, has been associated with fewer heart attacks, whereas heavy alcohol consumption increases CVD risk3. Despite the benefits of moderate alcohol intake, non-drinks should not be advised to drink, and adults with diabetes should be mindful of the risk of hypoglycemia, weight gain, and hypertension. No more than 1 drink/day for women and 2 drinks/day for men are recommended3. In America, 12-ounce beer or 5-ounce wine, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits are considered as one drink.

In addition to lifestyle management, intensive glycemic control can be valuable to prevent cardiovascular disease events in diabetes patients. Randomized trials involving intensive glucose control using insulin reported a 17% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), 15% reduction in coronary heart disease, 16% reduction in nonfatal MI, but no effect on stroke or all-cause mortality3. However, tight glucose control increases the two-fold risk of severe hypoglycemia and 47% risk of heart failure3. The research involving intensive glucose control using new anti-hyperglycemic agents is undergoing. Some newer agents are Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. DPP4 inhibitors inhibit the DPP4 enzyme, thereby prolonging the action of incretin hormone GLP-1 and insulinotropic polypeptide, which ultimately results in increased insulin secretion and lower glucose. DPP4 inhibitors agents successfully lowered A1C but showed no reduction in MACE, and one of the agents was associated with an increased risk of heart failure3. GLP-1 receptor agonist stimulates insulin release and slows down gastric emptying to decrease glucose absorption. The intervention with GLP-1 receptor agonists resulted in a significant reduction in MACE, heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular death; however, it had no beneficial effect on heart failure. The use of GLP-1 receptor agonists is associated with increased heart rate, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, thyroid cancer, and retinopathy. SGLT-2 inhibitors limit glucose reabsorption in the renal tubules3. SGLT-2 inhibitors lower the risk of hypertensive heart failure by 27-35%, MACE BY 11%, heart attacks by 11%, and cardiovascular death by 16%. SGLT-2 inhibitors are associated with genital and urinary infections, polyuria, acute kidney injury (with a higher dose), and reduction in bone mineral density3.

CVD risk increases with low and high blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes. When initiated at baseline (BP > 140/90 mmHg), Antihypertensive therapy resulted in CVD risk reduction but did not have a robust effect in type 2 diabetes patients compared to patients without diabetes3. ADA does not recommend a specific BP target but suggests risk classification to avoid overtreatment and polypharmacy3. In addition to BP abnormalities, an altered lipid profile is also a central risk factor for CVD in diabetes. The most common lipid abnormalities encountered in diabetes include:

- Increased serum triglycerides.

- Triglyceride-rich, very-low-density lipoprotein.

- Mild increase in small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C).

- Decreased HDL-C.

The lipid therapies include lowering LDL with statin/ non-statin, lowering triglycerides, and increasing HDL. Statin therapies reduce cardiovascular risk by 25%9, but HDL raising therapies had no effect3.

Lastly, clinical care only accounts for 10-20% of health outcomes; the rest 80-90% is contributed by social determinants, including socioeconomic factors, racism, environment, and individual behavior3. Therefore, we need a multifaced approach to address social determinants to eliminate disparities in CVD health. AHA recommends using a patient-centered approach and considering the patient’s family, community, and society while planning their cardiovascular risk management3. ADA and AHA have initiated a “Know Diabetes by Heart” program to improve CVD and outpatient care of type 2 diabetes patients. The program raises awareness about the link between diabetes and CVD, supports clinicians in patient engagement, and empowers patients3.

Reference

- National Diabetes Statistics Report. Accessed January 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html

- Cheng YJ, Imperatore G, Geiss LS, et al. Trends and Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Among U.S. Adults With and Without Self-Reported Diabetes, 1988-2015. Diabetes Care. 11 2018;41(11):2306-2315. doi:10.2337/dc18-0831

- Joseph JJ, Deedwania P, Acharya T, et al. Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. Jan 10 2022:CIR0000000000001040. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001040

- Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al. Update on Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Light of Recent Evidence: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation. Aug 25 2015;132(8):691-718. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000230

- Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Chiodini P, Panagiotakos D, Giugliano D. A journey into a Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review with meta-analyses. BMJ Open. Aug 10 2015;5(8):e008222. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008222

- Association AD. 5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes:. Diabetes Care. 01 2020;43(Suppl 1):S48-S65. doi:10.2337/dc20-S005

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 09 10 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 07 28 2016;375(4):311-22. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

- de Vries FM, Denig P, Pouwels KB, Postma MJ, Hak E. Primary prevention of major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events with statins in diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Drugs. Dec 24 2012;72(18):2365-73. doi:10.2165/11638240-000000000-00000

“The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately.”